Frisians: Meet the minority language and culture unique to northern Germany

If you’ve traveled around Germany a bit, you’ll likely have encountered some of the various dialects of German spoken in different regions.

But if you spend time in the northwest coast of the country, or venture over the border to the Netherlands, you may find yourself encountering a different language group altogether: Frisian.

Most closely related to English, three Frisian languages are still spoken today: West Frisian in the Netherlands, and Saterland Frisian and North Frisian in Germany. Around 60,000 people in Germany consider themselves to be Frisian, and somewhere between 8,000 to 10,000 speak North or Saterland Frisian.

While few people in Germany know much about the Frisians, understanding their story provides a glimpse into the diversity of German society, both historically and today.

So, who are the Frisians, how did the Frisian languages and cultures develop, and what efforts are being made to protect them today?

Frisian History: A Checkered Past

The Frisians first emerged in historical records as a Germanic tribe described by Roman historians about 2,000 years ago. Archaeologists later pieced together that this tribe lived in what is now the Netherlands. Frisians did not arrive in what is now Germany until about 1,000 years later, when they began settling further east along the coastline of the North Sea.

These Frisians lived quite an isolated, rural existence: they never formed a distinct political entity, or built a major city that could serve as a cultural center. Indeed, they were often more preoccupied by the stormy North Sea that threatened their coastal villages than the dukes of Schleswig and kings of Denmark who largely governed the territories where they lived, which after 1864 came under Prussian and then German rule.

READ ALSO: EXPLAINED: What to know about languages and dialects in Germany

This isolation helps explain the continued existence of Frisians as a distinct ethnicity, according to Nils Langer, Professor of North Frisian and Minority Languages at the University of Flensburg.

“Many minority languages and minority groups are often on the periphery of the geography. So if you think about the Bretons, the Basques, the Irish, the Scots, they are all on the fringes,” Langer told The Local. “The reason why the Frisians are where they are now, and have survived for 1,000 years as an ethnicity, is because nobody got there.”

Frisians did not always fly under the radar, however. In part because of their isolation, racial theories began emerging in the 1850s that claimed Frisians were one of the “pure” European races – an idea many Frisians believed. When the Nazis began promoting such ideas in the 1920s, Frisians, along with many Germans in rural areas who faced hardship at the time, supported these theories.

Friedeburg in Lower Saxony in winter. Photo: picture alliance/dpa | Hauke-Christian Dittrich

“It was presumably a welcome message when the Nazi party said, you Frisians are the edelrasse, you are purebreeds. [The Frisians] said, amazing: we are excellent, yes we believe that,” Langer explained.

But this privileged position in the racial hierarchy did not guarantee that Frisian culture itself would be protected.

“Once the Nazis came into power, lots of Frisians were disappointed, because the Nazis, whilst they liked pure blood, did not like minorities,” Langer said.

Frisians today: Three regions across two countries

The struggle to maintain and strengthen Frisian culture continues today. The Frisian identity persists in three separate regions: the Province of Friesland in the northern Netherlands, East Frisia in Lower Saxony, Germany; and North Frisia in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

Once every three years, West, North, and East Frisians from these regions gather on the island of Heligoland to celebrate their common ancestry and culture. Because the three languages aren’t mutually intelligible for most speakers, however, they typically speak English or German during this event.

“That in itself shows you how it is all Frisian, but it is actually quite far apart,” Langer said.

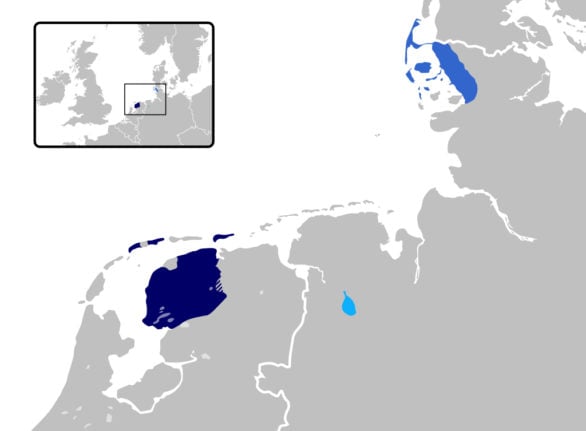

This map shows the areas where West-Frisian (purple), Saterland Frisian (light blue) and North Frisian (dark blue) are spoken today. Photo: Arnold Platon / Creative Commons

Indeed, these three regions are fairly distinct: each have their own unique culture and face their own challenges. In the Province of Friesland, about 400,000 of the 650,000 inhabitants speak West Frisian. The province also has small cities that have facilitated the emergence of a literary scene as well as West Frisian radio and television programs, which help strengthen the West Frisian identity.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of the estimated 60,000 Frisians in Germany live in rural areas. Around 50,000 of the 163,000 inhabitants of North Frisia consider themselves to be Frisian, and between 5,000 and 7,000 speak North Frisian. Only around 2,000 people across a few villages in East Frisia speak Saterland Frisian, the last remaining dialect of the East Frisian language. Outside this area, most East Frisians speak Low German.

READ ALSO: Thrifty Swabians and haughty Hamburgers: A guide to Germany’s regional stereotypes

There is no significant Frisian independence movement in Germany, but many Frisians are working to ensure their language and culture persist, even though others may not recognise its significance.

“If you are a minority, you constantly have to show that you’re important. Otherwise, people forget about you,” Langer said.

This is especially true for Frisians who speak German, and are largely assimilated into Germany.

“If you hear [Frisians] speak German, you wouldn’t be able to tell that they’re Frisians. They’re completely assimilated in that sense. And that kind of makes it difficult to retain their distinctiveness,” Langer explained.

Langer contrasted Frisians’ challenges in preserving a distinct cultural identity against other ethnic minorities in Germany, like Turkish people.

“Turkish people in Germany face other issues, in terms of racism. But they don’t have an issue of being forgotten, because they have strong ties and a distinctive identity,” he said.

Cultural celebrations and language promotion

One of the key ways that North Frisians mark their distinct identity is through biikebrennen, a community celebration that happens every year on February 21st. Last Tuesday, North Frisians gathered together to light bonfires up and down the coast. While the origins of this annual tradition remain disputed, it has been celebrated for at least 150 years, and serves as a way to unite North Frisians.

“It’s a really big event. [Biikebrennen] is the one thing that all North Frisians say: that’s part of us,” Langer said.

Frisians also receive funding and protection from the German federal and state governments through two international treaties that Germany signed in the 1990s. The first, the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, established the Frisians, along with the Danes, Sorbs, and the Sinti and Roma, as officially recognized minorities in Germany. The second, the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, recognizes North Frisian and Saterland Frisian as minority languages in Germany. Article 5 of the Schleswig-Holstein constitution stipulates the protection and promotion of Frisians as well.

A Biikebrennen celebration in North Frisia. Photo: Sönke Rahn / Wikimedia Commons

In addition to giving Frisians access to funding and support, these provisions also ensure that Frisians can communicate directly with their political representatives. In Schleswig-Holstein, for example, select members of the state parliament meet with representatives of the Frisian communities twice a year to hear their concerns. At such meetings, one topic emerges repeatedly.

“The one complaint that you always hear in those contexts is that more needs to be done to promote the language at schools,” Langer said.

READ ALSO: From Moin to Tach – How to say hello around Germany

While on some of the North Frisian islands, like Föhr, many children grow up speaking North Frisian at home, most will only have the opportunity to access the language through schooling.

Most politicians agree with Frisians that more can be done to promote language in schools, Langer says. This has changed dramatically since the 1950s and 1960s, when authorities encouraged parents not to speak Frisian at home because they believed it would confuse the kids, who were learning Hochdeutsch in schools.

The Frisian island of Wangerooge. Photo: picture alliance/dpa | Sina Schuldt

But despite this change in attitude, many feel politicians have not taken the issue seriously enough to take any real action to boost the teaching of North Frisian.

“If anything the number of pupils taking Frisian in school has declined over the last twenty years,” Langer explained. “Partly because the vitality [of the language] has reduced, but also because there are school closures, and with school closures, certain subjects that are small will then fall under the table, and Frisian is always the classic example.”

And while North Frisian has been taught in some schools for a while, in the Saterland region, they have only recently started to teach Saterland Frisian in primary schools, according to Langer.

Changing times: Tourism on the Frisian Islands

Another oft-discussed topic among Frisians today is tourism, which is how the majority of people from outside the area encounter the Frisian territories, especially North Friesland. While wind and solar energy have become important aspects of the economy as well, tourism remains a key industry. Islands such as Föhr and Sylt are especially popular. The creation of the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park in the 1980s has led to the marketing of the area for green tourism as well.

According to Langer, North Frisians have an ambivalent relationship to tourists. The money generated through tourism has boosted the economy and allowed many North Frisians to live a more comfortable lifestyle, but it has also meant a rise in housing prices on the island, many of which are bought by outsiders from cities like Hamburg or Berlin, and sit empty most of the year.

A windswept beach on the island of Sylt. Photo: picture alliance/dpa | Daniel Bockwoldt

This is especially an issue in Sylt, which attracts very wealthy tourists, Langer said. This has contributed to a narrative that North Frisians are being pushed off the island.

“The first railway station on the mainland from Sylt is Klanxbüll, and that’s where many Syltians live, people say. So many of the people from the island can’t afford to live on the island anymore, they live in the first village on the mainland, and then they travel by train to the island every day to work there, that’s the classic stereotype,” Langer explained.

In addition, North Frisians, like inhabitants of many rural areas, must contend with a lack of sufficient infrastructure, like hospitals or theaters, in the area. The bustling tourism industry has helped with this problem “a bit, similar to, say, the West coast of Ireland,” Langer said. “But when the summer season is over, it is very dark and cold in North Frisia.”

READ ALSO: What is Sylt and why is it terrified of Germany’s €9 holidaymakers?

Looking forward: Bringing Frisian culture to the younger generation

The main challenge going forward will be to continue demonstrating both to authorities and the younger population that Frisian culture and languages are worth studying, and securing the resources necessary to do so. Recruiting new teachers of Frisian is a key component in this process, and Langer said this has been difficult in recent years.

“We’re struggling with finding students. And our question is, is that a systemic [issue]? Is there anything we can do about it? There could be lots of different scenarios, and I hope it’s not because the young people don’t think it’s important,” he said.

When Langer tries to make the case to his students about the importance of studying Frisian, he makes two points. First, that “studying the Frisian community is pretty cool actually. [Frisian] has been there for a thousand years. People still speak it. There are little kids who speak it fluently. And it will outlast you.”

Second, it can give students perspective on different ways of living, and can also help them understand other minority cultures.

“It’s important to understand the ‘other,’” Langer said. “It’s important that people recognise that stereotypes are stereotypes, and not truths, and that the way we live isn’t normal, and that there are other ways of living.”