Archaeologists increase the prehistoric altars positioned within the Iberian Peninsula from 300 to 1,300 | Culture | EUROtoday

They are often known as sacred rocks and are rock formations that in historical occasions had been believed to have a “supernatural” character and “magical” connotations. They are associated each to animist beliefs originating within the Paleolithic and to others that emerged within the Neolithic, in addition to to myths of Indo-European origin typical of the Atlantic Celts. Curiously, its “magic” nonetheless survives in common traditions repressed throughout Christianization, the Muslim invasion and the Enlightenment. “It is a long-lasting phenomenon,” as outlined by the archaeologist of the Royal Academy of History Martín Almagro Gorbea in his article The sacred rocks of the Iberian Peninsula, revealed within the scientific journal Completeness. The quite a few investigations carried out lately – amongst others, by specialists reminiscent of Julio Esteban Ortega, José Antonio Ramos Rubio or Óscar de San Macario in Extremadura; Fernando Alonso Romero in Galicia; Jesús Caballero in Ávila; Ignacio Ruiz Vélez in Burgos, and Ángel Gari within the Huesca Pyrenees, have managed to extend the variety of positioned sanctuaries from 300 in 2005 to greater than 1,300 presently. The abandonment of the countryside and the brand new infrastructures threaten them with dying, so we must always proceed, Almagro claims, with the rapid safety of those “archaeological and ethnological monuments in the face of their serious risk of disappearance, since they are an important part of the Cultural Heritage of Europe ”, along with being an untapped vacationer useful resource.

These rocks, principally siliceous, had been used to current sacrifices to the god or ancestral spirit that inhabited them, which may very well be each female and male. It was believed that they favored fertility, well being, data of the long run, the right functioning of society, set the suitable date for rituals and festivities and helped to get pleasure from, amongst different virtues, favorable climate in every season.

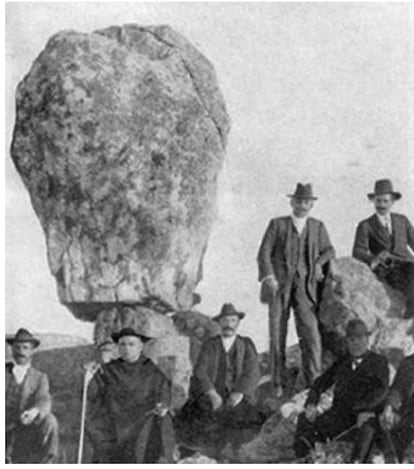

“During the 20th century they were forgotten due to exaggerations celtomaniacas of the antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries, but they have once again been valued as archaeological and ethnic elements thanks to studies that combine ethnological, archaeological data, classical and historical texts, history of religions, mythology, toponymy and archaeoastronomy,” says the expert.

“If the myths are lost, the sacred rocks lose their value”, Martín Almagro

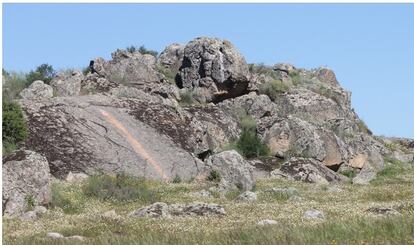

Their study shows that the sacred rocks “do not offer special physical characteristics, nor do they constitute a prominent point of the landscape, although they are usually in solitary places that stimulated the perception of sacredness, so it is the rites and myths associated with them that allow us to know if they are sacred. If those myths are lost, they lose their value.” In fact, this emeritus professor of Prehistory at the Complutense University emphasizes, “for rural people, until recently, every sacred rock had supernatural powers, since it was implicitly considered inhabited by a superior spirit, a belief that undoubtedly comes from from ancient times.”

They have their origin in animist beliefs that have lasted until today as more or less Christianized superstitions. “As Christianity spread, these traditions were persecuted as pagan beliefs, but their rites and myths survived because they were deeply rooted in the popular mentality.”

The sacred peña is a very simple and different element from the concept of a sanctuary, which requires specialists or priests to inhabit or care for it. “This simplicity is reflected in their rituals, always personal and carried out by those who carry them out without the collaboration of intermediaries. [sacerdotes]; in any case with a family companion, such as the partner for fertility rites or the child who wants to be healed.”

As these practices spread over time, they were considered pagan superstitions and their destruction and oblivion was encouraged, although this did not prevent their use far from urban environments. Beginning with the Renaissance, some humanists identified sacred rocks and megalithic monuments as “sacrificial altars” that they attributed to the Celtic druids. This interpretation was supported by the enlightened antiquarians of the 18th century, who also considered them Celtic monuments within a “Celtomania” that reached its peak in 19th century Romanticism. Dolmens, menhirs, rocks with buckets and cavalry rocks were inevitably attributed to the Celts and were interpreted as “druidic altars”, magical in short. Therefore, the Enlightenment tried to suppress them.

However, the panorama has changed in the 21st century, Almagro recalls, as studies on these monuments have increased: “The key has been to use an ethnoarchaeological methodology with a historical perspective to analyze their origin and cultural context. Traditional ethnological and anthropological studies gave an anachronistic vision that did not understand the mentality of those who used the sacred rocks. These beliefs can only be explained as the fossilization of rites, myths and traditions of prehistoric origin in a long-lasting process, which rural society had preserved associated with the microtoponym that designated each rock, which has been lost when the countryside was depopulated and all this disappeared. culture of ancestral origin.”

The sacred rocks of the Iberian Peninsula are classified into 24 types that make up six large groups according to their function: numinical (in which a numen or spirit lives), rock altars, propitiatory, fertilizing, healing and related to the organization of society. Within each group there are several types, and some may belong to different groups.

In Portugal 233 have been identified, in Galicia 230, in the area of Zamora and Salamanca 154, in Extremadura 260, in Ávila 267 and in Madrid, Toledo and Ciudad Real another 40, in addition to other important groups in Burgos and the Basque area -Pyrenean. This means one sacred rock every 30 square kilometers. Most are in siliceous and rural areas, approximately what Celtic Hispania was, which spanned from the Iberian System to the Atlantic.

Although not all types of rocks or all rites have the same chronology or the same origin, as a whole they reflect beliefs of a very primitive nature, spiritual forces superior to human beings and related to ancestors. When they became Christian, they began to identify themselves as the Devil, the Virgin or some saints.

Specialists believe that its origin dates back to the Bell Beaker Period (Third Millennium BC), although they do not rule out even greater antiquity, as occurs in the so-called “sliding rocks” rite, related to fertility. These are flat stones inclined, between 25 and 50 degrees, through which women fell to become pregnant. This tradition is typical not only of the Iberian Peninsula, but also of Western Europe, from France to Switzerland, but also in Greece or North Africa.

Examples of the survival of these customs are numerous. Almagro remembers that in the Basque Country, until the year 1326, the lords of Vizcaya sacrificed cows on a rock to their tutelary goddess. This functional and mythical continuity is also witnessed by many other cases, such as the Celtic altar, the Mozarabic chapel and the baroque church of San Miguel de Celanova (Orense), all three aligned, which proves that in rural areas these monuments have continued in use. practically until today, but converted into legends with deep popular roots.

An 8th century church on a dolmen

Esperanza Martín, director of the Lucus Asturum site and specialist in protohistoric constructions in the Cantabrian area, admits that there is an “undoubted” relationship between these altars “with telluric sites, which end up becoming popular beliefs.” “In Cangas de Onís, on the dolmen of Santa Cruz, in the times of Favila [siglo VIII], a church was built, because it was a sacred site. Human beings have always considered certain places sacred. In 2017, a countryman who heard the legend that the last ray of winter in Cardiellu [Asturias] marking the location of a treasure, he found just where the sun indicated a Palstave ax from the Bronze Age, one of the so-called heel and double ring axes. There are dozens of examples on the peninsula. All legends have a meaning and preserve a story. Almagro has been recovering hundreds of these places for years.”

Daniel Gómez Aragonés, member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Historical Sciences of Toledo, considers the relationship between popular traditions and these “magical places” “undeniable.” “In the Visigothic era, many pilgrimages were created that were based on eminently Celtic customs. If you add the element of water to these places, fundamental in Celtic culture, Christianity immediately turns them into places of worship for Saint John the Baptist or the Virgin Mary. There are hundreds all over Spain,” he says. Gómez Aragonés, who describes Almagro as the pinnacle of this type of research, recalls that he already demonstrated the connection between the Legends by Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer with this disappeared culture in his book Celts. Imaginary, myths and literature in Spain.

But these stone monuments, the academic's article concludes, “are in a remaining technique of disappearance as a result of depopulation of the countryside and the profound cultural change of agrarian society within the final two generations of the twentieth century.”

And it ends: “They must be preserved as authentic monuments of great historical and cultural interest before they disappear definitively when they are forgotten or destroyed, since they testify to ancestral rites of the prehistoric past that European culture has preserved in its folklore, which is why they form an essential part of its archaeological and cultural heritage.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to proceed studying

Read with out limits

_

https://elpais.com/cultura/2024-02-24/los-arqueologos-elevan-de-300-a-1300-los-altares-prehistoricos-localizados-en-la-peninsula-iberica.html