Both glory and dishonour for the French military | EUROtoday

On May 18, 1944, Allied troops captured Monte Cassino in Italy, celebrated for its historic hilltop abbey, after 4 months of bitter combating. The troopers of the French Expeditionary Corps significantly distinguished themselves within the battle for this key level within the German defensive position. But their army honours at the moment are marred by accusations of struggle crimes.

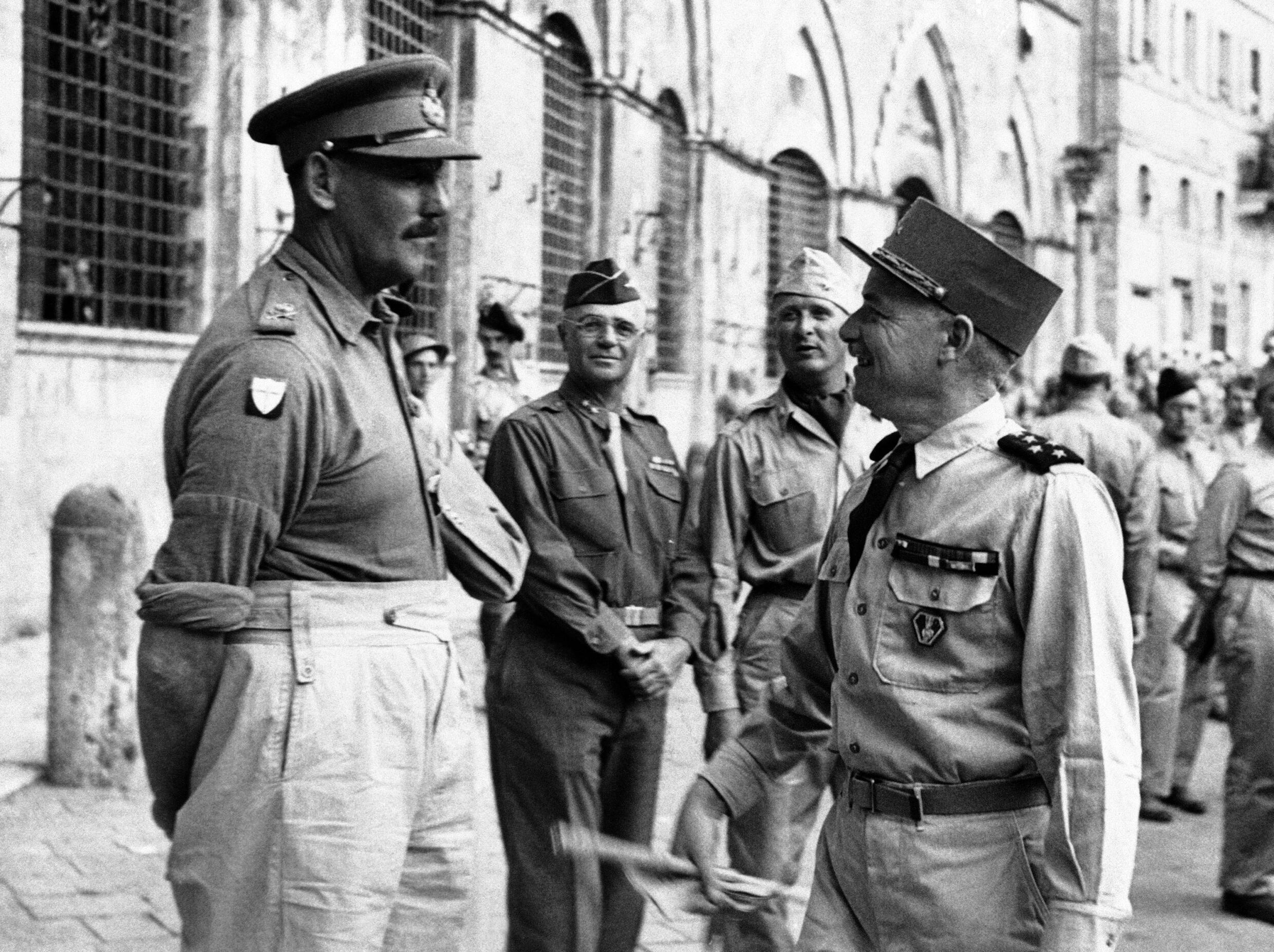

“Garigliano is a great victory… France will know one day. She will understand.” On the night of his departure from Italy in August 1944, French General Alphonse Juin spoke these phrases to his officers, underlining how decisive the crossing of the Garigliano River by his males had been for the Allies. Thanks to this breakthrough, the Germans lastly deserted Monte Cassino after 4 months of intense combating. The street to Rome was lastly open. But 80 years on, General Juin’s heartfelt sentiments haven’t been fulfilled. The Italian marketing campaign has regularly light from the collective reminiscence.

After the landings in Sicily and Calabria in September 1943, the Allied forces have been slowed down in Italy. The Germans held agency, protected by the Gustav Line which stretched for 150km throughout the Italian Peninsula and barred the way in which to Rome.

“Monte Cassino was one of the bulwarks in the defensive system of the German armies. It was an important observation point, enabling them to keep Allied attacks at bay,” explains historian Julie Le Gac. “The Allies tried every possible way to break through this line, with waves of assaults that have been likened to trench warfare. It was referred to as the ‘Verdun of the Second World War’.”

‘One of the most brilliant military feats of the war’

Between January and May 1944, Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line defences were attacked on four occasions by Allied forces. France contributed troops from the French Expeditionary Corps (CEF), comprising units of the African Army, colonial troops and Free French forces. “Sixty percent of this army was made up of colonial soldiers, mainly North Africans – Algerians and Moroccans, but also Tunisians,” explains Le Gac, creator of “To conquer without glory: the French expeditionary force in Italy” (“Victory with out glory: The French Expeditionary Corps in Italy”).

These troopers had already fought with distinction in early 1944. “The 4th Regiment of Tunisian Riflemen accomplished one of the most brilliant military actions of the war, at the cost of enormous losses,” General Charles de Gaulle wrote in his memoirs. The regiment captured the Belvedere plateau close to Monte Cassino after fierce combating between January 25 and February 1. Despite this victory, the Gustav Line remained intact. General Juin then devised a daring technique, selecting to launch his assault by means of the Aurunci Mountains, thought of by the Germans to be impassable.

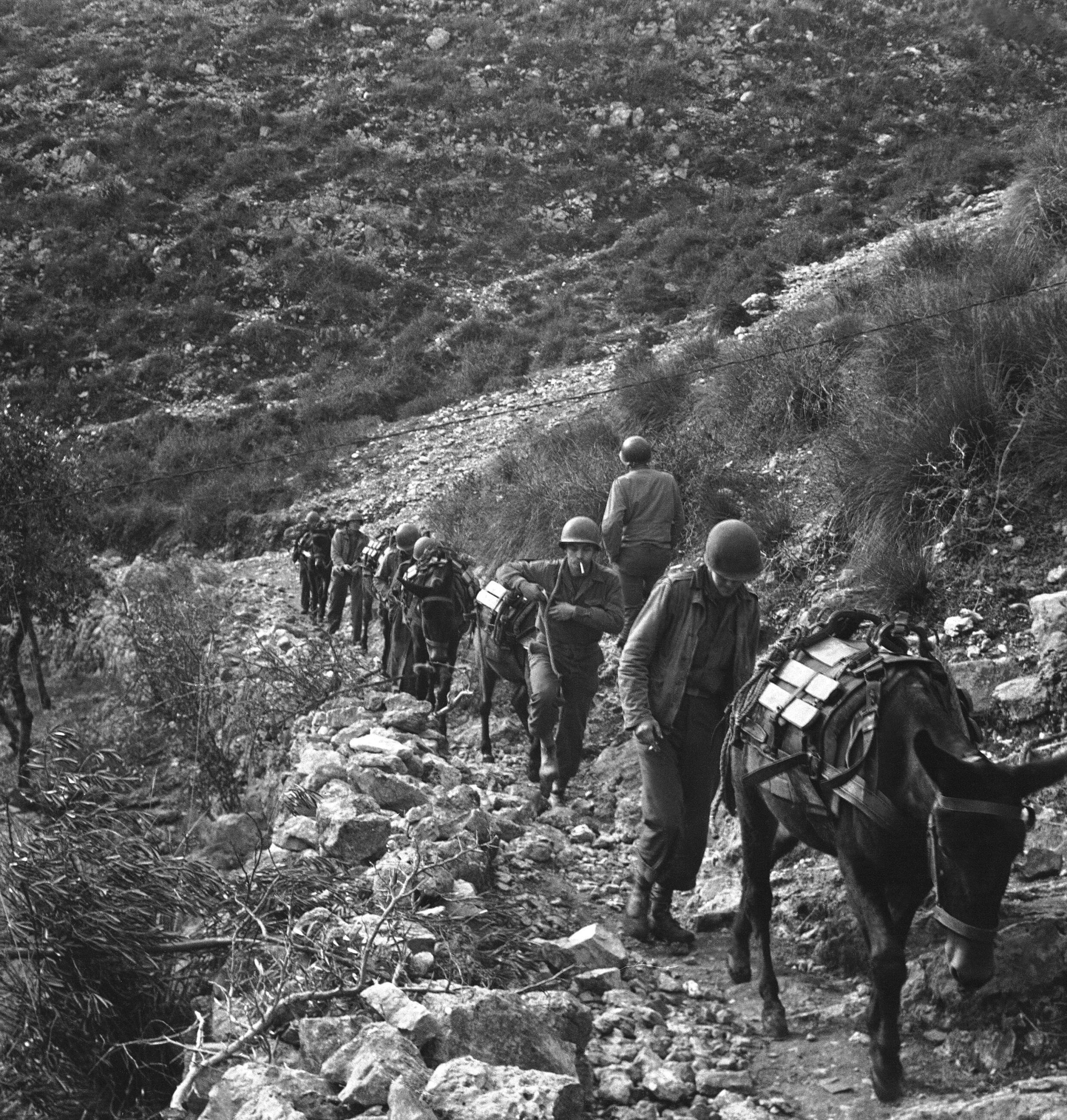

His offensive manoeuvre relied on the mountain combating abilities of the troopers from North Africa, significantly the Moroccan “Goumiers”, because the troopers have been identified, who have been used to tough terrain. “These were really goat trails. They managed to get divisions carrying all their equipment and machine guns over these paths on mules. These men were mountain specialists. It was an extraordinary coup by General Juin, who I consider to be the greatest French military strategist of the war,” says historian Jean-Christophe Notin, whose books embody The Italian Campaign 1943-1945 (“The Italy Campaign, 1943-1945”).

Ten thousand Goumiers penetrated the Aurunci Mountains and in three weeks eradicated the entrenched German items, lastly enabling an advance in the direction of the Italian capital.

“The French, and above all the Moroccans, fought furiously and exploited every success by immediately concentrating all available forces on the most vulnerable points,” wrote German General Albert Kesselring in his notebooks on the time.

On June 4, 1944, the Allies lastly entered Rome. But this victory was overshadowed by the Allied landings in Normandy, which came about two days later. “It marked the rebirth of the French armies, but it was completely overlooked. I’m not sure many people know what Garigliano means,” says Notin.

Mass rape

In Italy, then again, the involvement of the French expeditionary corps continues to be vividly remembered, however for its prison acts. A generic phrase even refers to them: “Moroccan”, or “Moroccans’ deeds”. It refers back to the mass rapes dedicated by French military troopers between April and June 1944 within the Ciociara area, southeast of Rome. These struggle crimes have been attributed, because the time period suggests, to the Moroccan goumiers of the CEF – though solely one among these troopers was subsequently convicted of such expenses.

The British author Norman Lewis, then an officer on the Monte Cassino entrance, described the violence in his 1978 e book “Naples 44″: “French colonial troops are on the rampage again. Whenever they take a town or a village, a wholesale rape of the population takes place.” Vittorio De Sica’s 1960 film “La Ciociara” was additionally impressed by these occasions. Adapted from Alberto Moravia’s novel and starring Sophia Loren within the Oscar-winning title position, it recounts the tragedy of a mom and daughter raped by Moroccan Goumiers.

In her e book, Le Gac examines this extremely delicate situation. “These crimes were of considerable magnitude,” she notes.

The historian estimates that between 3,000 and 5,000 rapes have been dedicated by the CEF throughout your complete Italian marketing campaign, though this quantity is the topic of debate amongst researchers. She factors out that previously, and even as we speak, ladies have been perceived as “spoils of war”. According to Le Gac, these mass rapes will be defined by the “extreme violence of the fighting” resulting in psychological trauma for combatants, but additionally by a flawed chain of command with “insufficient supervision”.

Among the Italian inhabitants, it was rumoured that General Juin had granted his troopers 50 hours’ depart after the battle, giving them a inexperienced mild to prey upon the native inhabitants. But no file of such an order has ever been discovered, as Le Gac explains: “After the war victims’ associations claimed to have found a written order, it was found to be a forgery. In any case, these are not orders that would be given in writing, and I don’t really believe in them.”

For these acts of sexual violence, 207 CEF troopers have been introduced earlier than French army courts. In all, 156 troopers have been convicted (87 Moroccans, 51 Algerians, 12 French, three Tunisians, three from Madagascar), however solely one among these was recognized as being a Moroccan Goumier.

For Le Gac, this will imply that they got abstract justice. In addition to those convictions, 28 troopers whose unit affiliation is unknown have been executed.

Notin remembers discussing this topic with veterans of the Italian marketing campaign: “Most of the time, the guilty parties were shot directly or more cruelly, they were told to leave the French lines, unarmed, and march toward the Germans. That’s how they were killed.”

But Notin additionally believes that the Moroccan troopers made handy culprits. In his opinion, they have been removed from the one perpetrators of atrocities and have been additionally topic to racism: “There was a lot of propaganda on the part of the Italians to denigrate the victors by making them out to be ignorant and uncouth men.” After the First World War, a propaganda marketing campaign, identified within the English-language press because the “Black Horror on the Rhine”, was additionally launched in Germany in opposition to the presence within the Rhineland of troopers from the French colonies, Notin recollects.

However, Notin doesn’t deny the fact of those mass rapes, which he estimates at between 300 and 1,000: “When I wrote my book, people asked me if I was sure I wanted to talk about it, but if you want to pay tribute to the combatants, you have to talk about all the facts. If you let them go unmentioned, it’s as if you were complicit in them and approved of them.”

Exploitation by Italy’s far proper

Eighty years after the occasions, the topic continues to be controversial in Italy. In 2018, a stele paying tribute to 175 CEF troopers killed in motion was vandalised within the village of Pontecorvo, close to Monte Cassino. Three years later, Pope Francis was criticised for visiting a French army cemetery in Rome the place 1,200 troopers who died through the Italian marketing campaign, together with Moroccan Goumiers, are buried.

France has compensated almost 1,500 victims however has not issued an apology for the mass rapes. Italians are nonetheless demanding justice, together with members of the National Association of Victims of Marocchinate (“National Association of Victims of the Maroccochinate”). “Unfortunately, these initiatives are highly politicised,” says Camilla Giantomasso, a researcher on the University of Rome and creator of a thesis on the reminiscence of the Moroccan. “They are ideological proposals that only find fertile ground in far-right parties that see African troops as scapegoats for what happened, whereas responsibility should in fact be extended to Franco-European troops and the Allies in general, and understood in the overall context of the war.”

In 2023, Senator Andrea De Priamo, a member of the Brothers of Italy social gathering of far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, launched a invoice to determine a nationwide day of remembrance for victims of wartime rape. The regulation even places ahead the determine of 60,000 rape victims, which is disputed by historians.

“In the logic of far-right parties, this remembrance is particularly useful because, in the end, those responsible for what happened have always been identified as ‘Moroccans’ – in other words, non-Western people of colour”, Giantomasso says. “This is something that they don’t hesitate to link to current African migrants who, in their eyes, seem extremely dangerous, precisely because of this past. Unfortunately, although this is an anachronistic view and lacks historical rigour, it resonates with many people who don’t want to delve into what really happened and limit themselves to a superficial reading of the phenomenon.”

For Giantomasso, the occasions are nonetheless “a conflicted and difficult memory”. But as famous by Canadian historian Matthew Chippin, who wrote a dissertation entitled “The Moroccans in Italy: A study of sexual violence in history”, these long-neglected struggle crimes are more and more the topic of examine.

It is a posh situation that deserves a lot higher investigation, in accordance with Chippin, a researcher from the University of Leeds. The occasions that led to the origination of the time period “Marocchinate”, he says, “do not just concern victims and aggressors, but two marginalised peoples. On the one hand, there are the Italians, who suffered terribly during the war, and on the other, the Moroccans, who were treated like primitives and often looked down upon.”

This has been translated from the unique in French.

https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20240518-the-battle-of-monte-cassino-both-glory-and-dishonour-for-the-french-army