World War II veterans go away their kids a legacy of trauma | EUROtoday

The trauma skilled by World War II veterans of D-Day left an enduring affect on their kids at a time earlier than post-traumatic stress dysfunction (PTSD) was recognised, leaving households struggling to know and address the psychological scars. Recent gatherings of consultants in Normandy spotlight each the enduring challenges and the resilience that was handed down by way of generations.

For the largest seaborne invasion of World War II – alongside Normandy’s shoreline on June 6, 1944 – to be a hit, three vital circumstances needed to be met. There had to be a full moon, so Allied paratroopers may have extra visibility when touchdown. The tide needed to be low sufficient that 1000’s of amphibious touchdown craft may attain the shores of Utah, Omaha, Juno and Sword seashores. And a morning fog on the horizon was wanted to cover the arrival of Operation Overlord from German forces.

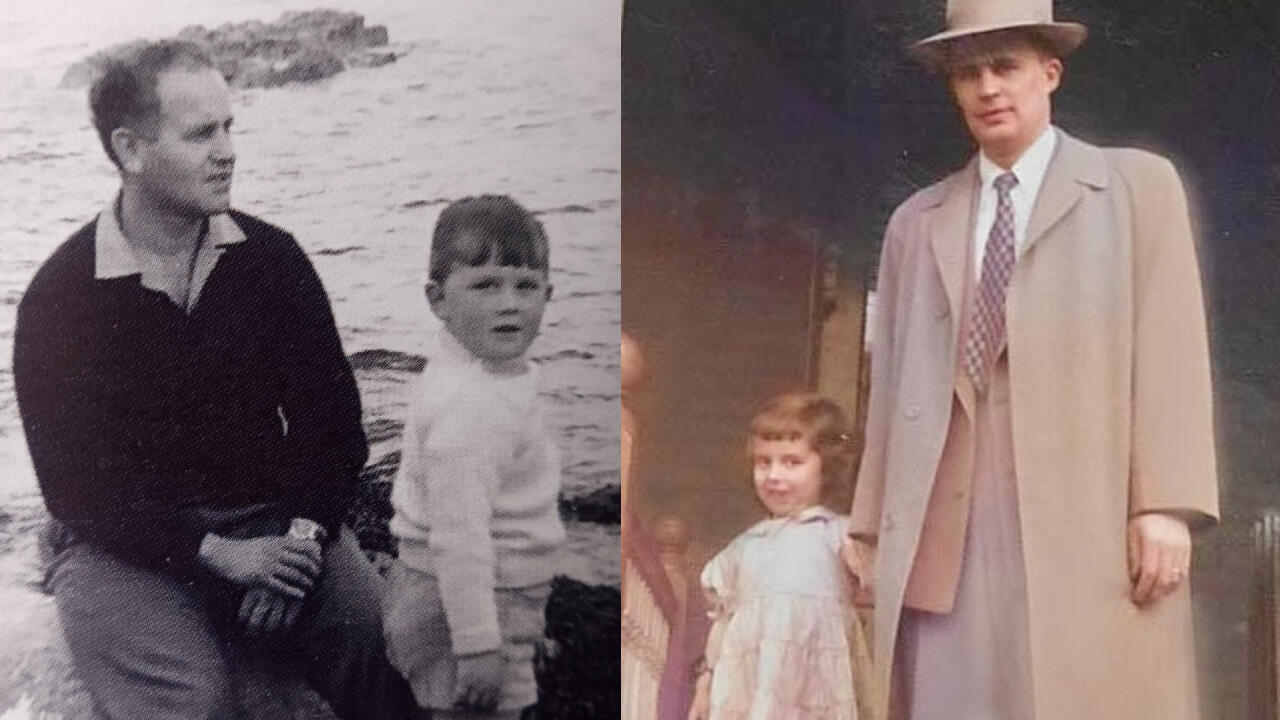

They didn’t realize it on the time, however what US paratrooper Arthur ‘Dutch’ Schultz and British Royal Marine Thomas Nicholls skilled on D-Day would outlast their lifetimes. Both males returned to their houses with various levels of post-traumatic stress dysfunction. They struggled with signs like intrusive ideas, irritability, nervousness, despair and nightmares. While the 2 veterans handled their ache otherwise, their situation had an enduring affect on their households and particularly on their kids.

On May 21, 30 consultants from all over the world gathered on the historic websites of the Normandy landings to debate the lasting psychological well being penalties of traumatic occasions like D-Day. Though PTSD is now a broadly recognized situation, battle trauma took many years to turn out to be recognised by the medical career. And researchers have discovered that, even when veterans like Schultz and Nicholls have now handed, their kids nonetheless bear the indicators of getting grown up with a traumatised mother or father.

As a thick fog begins to set on the horizon, the low tide swells out and in, tickling the shores of the shoreline. Eighty years after the landings occurred right here in Normandy, the climate circumstances are uncannily just like that fateful day again in June 1944.

‘We were all sort of clueless’

Post-traumatic stress dysfunction was solely formally recognised many years after WWII veterans ended their service, within the wake of the Vietnam War. It first appeared within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), revealed by the American Psychiatric Association to outline and classify psychological issues, in 1980. For the practically 160,000 Allied troops who landed in Normandy in 1944, the dearth of a prognosis or framework made it tough to hunt correct therapy.

Before PTSD was recognised, it glided by many different names. After World War I, PTSD signs equivalent to panic, tremors or sleep points had been often called “shell shock” and seen as a direct response to artillery shells exploding. “War neuroses” was one other identify given to the situation on the time, in addition to “combat fatigue”. Both phrases mirrored the prevailing perception that when a soldier was now not on the entrance line and had time to loosen up, his war-related trauma would disappear. As a end result, troopers typically obtained only some days of relaxation earlier than returning to battle.

Read extra‘Taboo’: French girls communicate out on rapes by US troopers throughout WWII

Dominant theories to elucidate battle trauma earlier than 1980 had been based mostly on Freudian psychoanalysis. According to this method, the primary purpose veterans had psychological points was repressed childhood emotions of tension and hostility, woke up by their expertise of battle. The horror of fight was not thought-about an impartial explanation for psychological trauma. Instead, it was assumed that troopers already had emotional points earlier than their service.

“[Now we know] that in order for someone to develop PTSD, they have to experience a life-threatening traumatic event,” explains Dr. Sonya Norman, professor of scientific psychology on the University of California San Diego, who travelled throughout the Atlantic to share her expertise working with PTSD sufferers. “Someone could have a genetic predisposition to PTSD but if they don’t experience this kind of event, they will never develop it.”

Dangerous societal myths within the post-war period additionally contributed to stifling the legitimacy of PTSD as a critical dysfunction. “People would say veterans were just ‘nervous from the service’ or even tell them that: ‘The war is over, buddy, get on with it’,” sighs US paratrooper Schultz’s daughter, Carol Schultz Vento. The dominant discourse on the time was that of the “Greatest Generation”, who fought heroically in what was often called the “Good War” and returned from battle wholesome and well-adjusted.

Portrayals of World War II on the silver display screen had been additionally removed from what servicemen had skilled on the bottom. Vento’s father, a US paratrooper, was portrayed by the actor Richard Beymer within the 1962 movie, “The Longest Day”. But the narrative didn’t replicate the actual horrors her father witnessed on D-Day. His younger and hapless character will get misplaced after being dropped on the unsuitable location and by no means appears to succeed in the energetic fight round him. “I only found out 30 years later that yes, he was lost, but he was actually at battle,” a shocked Vento admits. After making contact with different misplaced troopers on June 6, Schultz got here beneath violent fireplace and even witnessed the chilling mercy killing of a wounded US compatriot.

For many WWII veterans and their kids, it wasn’t till Steven Spielberg’s 1998 battle epic “Saving Private Ryan” that the trauma of their expertise was unveiled. “My father said it was the most realistic movie he had ever seen in terms of actually demonstrating what happened in the war,” says Vento.

Secondary trauma

“[PTSD] is a significant mental health issue and it impacts the way you parent. And then your children suffer because of that,” says Diane Elmore Borbon, govt director of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), whereas strolling the dunes of Utah Beach. “People didn’t realise that there were consequences they could pass down to their children and even grandchildren.”

Vento is now 72 years outdated and lives in New Jersey. Her early recollections of her father are of a person who “drank, but was highly functioning”, a “good and involved father”. As a baby, her dad would play marching video games along with her and her sister, so she knew that he had been a solider. But “he didn’t talk about it very much”, she says.

It was solely at round age 13, when Vento’s mom and father divorced, that she started to see her father’s signs worsen. “He slid down into a much more severe alcoholism and depression … he basically fell apart,” she describes. Going out and in of rehab, her father grew to become distant. He tried suicide. He had recurrent nightmares. He missed vital moments of Vento’s life, like her highschool commencement. But she understood that to a sure extent, it was not his fault. Following their divorce, her mom had defined that her father had, in actual fact, been fighting trauma signs for the reason that first day of their marriage.

“I was hurt and I felt somewhat abandoned. But at the same time, I felt sorry for him,” she says.

The discipline of intergenerational trauma remains to be comparatively younger. After PTSD was formally recognised in 1980, researchers began its affect on the households of battle survivors and veterans. Studies on the youngsters of Holocaust survivors urged that they had been deeply affected by the trauma of their dad and mom. But analysis on the households of World War II veterans with PTSD has been a lot sparser. A 1986 examine by Robert Rosenheck, professor of psychiatry on the Yale School of Medicine, discovered that some kids appeared “embroiled in a shared emotional cauldron” with their fathers. Of the dozen kids he studied, some over-identified and skilled “secondary traumatisation” whereas others had been aloof and selected to distance themselves.

“I became the rescuer,” Vento explains, “which is a big burden. When you are going through something [tough in life], you think it is normal. But I didn’t realise until after a lot of therapy that it is really parentification,” a phenomenon the place kids tackle caregiving obligations on the expense of their very own developmental wants.

It was solely when Vento was in her 40s, throughout her first foray into psychotherapy, that she started to know how her father’s trauma had formed her. “My therapist asked me how I felt and I said: ‘What do you mean by ‘feel’?’ I was very repressed. I could not even express how I was feeling.”

Up till that time, Vento had coped along with her feelings by burying herself in her research. “I told my therapist that I thought I was addicted to education. He said yes, but that I was essentially trying not to deal with my suppressed emotions,” she explains.

It was solely a 12 months and a half in the past, at age 71, that Vento started trauma remedy after her daughter urged she discover a specialised counsellor.

“I have been told I definitely have secondary PTSD,” she says.

The transmission of resilience

In the late Sixties, Vento’s father Schultz ultimately turned his life round. He bought sober and spent the remainder of his profession because the director of drug and alcohol rehabilitation programmes in Philadelphia.

“There is incredible resilience in these families,” ISTSS director Borbon explains. “For a lot of people, war experiences help them find meaning in their lives. At a young age, they knew what it was like to lose people.”

British soldier Thomas Nicholls was solely 19 years outdated on D-Day. Though he didn’t participate in front-line energetic fight on the June 6, 1944, he witnessed grotesque scenes. After Operation Overlord was nicely beneath approach, the younger soldier was ordered to retrieve our bodies from the ocean, which his son Philip says was the worst reminiscence his father had of the battle.

Read extraFamily of celebrated French WWII veteran Léon Gautier refuses the commercialisation of his legacy

But the now 62-year-old didn’t know any of this till he was nicely into his 20s and commenced to take an curiosity in his father’s previous. Once per week, Nicholls would carry his father to the pub and purchase him a number of drinks. Over time, he started to open up and share experiences of his previous as a younger serviceman in World War II.

“I wanted to know more,” says Nicholls. “I wanted to know why he repressed it for 40 years.”

Nicholls describes his childhood relationship along with his father as “very much one of distance”. The pub conversations fostered proximity, a way of connectedness, and ultimately reworked their relationship. Down the road, nonetheless, his curiosity grew to become “an obsession”. And although he has not felt significantly anxious, depressed or pressured all through his life, Nicholls admits that this obsession stood in the best way of his household life. “It ruined my first marriage,” he says.

Though researchers haven’t recognized a PTSD gene per se they’ve discovered some genetic predisposition to trauma, despair and nervousness normally. “We have seen multi-generational effects of trauma, whether that is nature or nurture, we can’t say,” Dr. Norman explains. “We know that there are higher rates of depression, anxiety and stress among children who are raised with PTSD. The experiences of that child could predispose them to be more likely to have those conditions later on in life.”

Looking again, Nicholls regards his father’s stoicism with satisfaction. “I am amazed he was able to hold that in for four decades,” he says. Though he says he didn’t inherit any trauma, he says he will get his power from his dad. “I learned how to cope,” he beams.

Despite the resilience his father handed all the way down to him, Nicholls says he would have appreciated to have had extra “good years” along with his father. “I had 25. I would have liked 45,” he says gently, tears forming in his eyes.

As the consultants are ushered again into the coach to go to the following D-Day web site, Borbon seems to be again on the shores of Utah Beach fondly. With a sparkle in her eye, she underscores the optimistic results of the transmission of resilience that may include rising up with a war-traumatised mother or father.

“At the end of the day, society needs bravery. And thank goodness there are people in the world who step forward,” she says.

https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20240527-world-war-ii-veterans-leave-their-children-legacy-trauma-d-day-anniversary-normandy