‘The Requester’, an acidic diary a few author who cleans rooms to outlive in Berlin | Culture | EUROtoday

He writes his memoirs, recites poetry, organizes cultural occasions and cleans bogs. Leyla, the protagonist of The Applicant (Mapa publishing home), the debut novel by the Turkish Nazli Koca, born in Mersin—so elusive for some questions, that she defines herself as “in her thirties” and about whom pictures are scarce—combines her literary aspirations together with her job as a cleaner in a hostel embellished in Alice in Wonderland from Berlin. Leyla is the allegory of so many declassed immigrants and victims of the mirage of meritocracy.

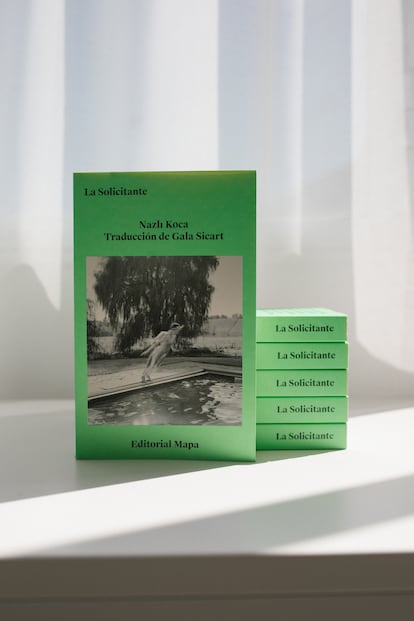

The protagonist can be a transcript of the creator’s experiences within the German capital. Koca, additionally Turkish, hooked on her nation’s cleaning soap operas, had a sophisticated relationship with Berlin. She additionally moved to the German capital to jot down, disenchanted with Istanbul and her job as a publicist. “Loss, the lack of roots, makes you cling to hope, to the possibility of belonging to a place, even if everything seems lost and things get complicated,” he says in a digital interview, wherein he warned that such Maybe she would join with out turning on the digicam. It wasn’t like that. Koca receives smiling from Denver, Colorado, the place he resides, with a white shirt; behind him, the Spanish model of his novel, translated by Gala Sicart and revealed in September.

She has labored as a cleaner, dishwasher or bookseller. She is aware of disappointment, she has additionally realized, in her 10 years as an immigrant, that social justice is a fantasy. Under the format of a diary, his novel slaps the reader within the face from the primary pages: Alí, a graduate scholar, unpaid professor with three jobs, Turkish, provides Leyla some latex gloves, together with an eloquent greeting: “Welcome to the “lowest in the immigrant hierarchy.” Koca, like her protagonist, began writing a diary on her first day as a cleaner. “It has been a enjoyable problem to adapt it right into a novel, discovering the purpose between those that anticipate a precise copy of the style and people who desire a extra elaborate model. The diary right this moment is greater than a pocket book: it’s notes on the cell phone, Google paperwork, scattered pages…”, he says.

Leyla loses the right to a student visa after failing her doctoral thesis—by a professor who until then “had approved everyone”—and is trapped in a bureaucratic labyrinth, in a legal category whose name sounds like a joke: Fiction certificate (fictional certificate, in German). If the professor does not change the grade or the court to which he has appealed does not rule in his favor, he must return to Türkiye. However, Leyla does not want to return to a country in a state of emergency where “Erdogan [presidente de la República de Turquía] has all the power to do whatever he wants,” where adults are “lonely addicts” and “young people don’t commit suicide because they are too busy trying to survive.” “When you are a migrant, you have to be either a genius who works at Google, or get married, even if you don’t believe in marriage, so that nationals can see you in the transition to their citizenship,” he says. To overcome difficulties, the narrator applies acidic and cheeky humor.

The title and the letter with which the book opens rewrite the poem The Applicant (The Applicant), by Sylvia Plath. “Give me two coins and I will work proudly in your filthy hospitals, universities, and technology companies. I will live in your apartments and take care of your babies. Free. I will be your cheap whore, here and now,” writes Koca, who avoids social networks. “I recognize their advantages, but, in my opinion, they hinder writing. People become obsessed with getting likes. Another danger is the immediacy of sharing thoughts that have not yet matured, which can hinder the development of ideas and ruin the essence of the creative process.”

The author connects with a genealogy of writers who have unmasked the fallacies of the meritocratic capitalist system: Eva Baltasar, in Decline and fascination (2024); Brenda Navarro, in Ash in the mouth (2022); Noelia Collado, with exhausted mares (2023); Claudia Durastanti, in The foreigner (2020)… Koca triggers experiences while unraveling thoughts. Men “have managed,” he states in the book, “to make us believe that […] They do not owe us anything after centuries of captivity in their homes, forced to do all kinds of domestic tasks without receiving anything in return. How did they achieve it?” “It is impossible to separate the personal from the political. If you check the news on your phone before sitting down to write, it’s hard not to reflect on what’s happening in the world.”

Asked if she is worried concerning the excessive proper within the European Union and the potential opening of facilities outdoors the EU to expel those that want to enter group territory, she responds: “The tightening of immigration legal guidelines is terrifying. Immigrants are sometimes the scapegoats for all issues. “It is just not sufficient that they’re those who are suffering essentially the most in pure disasters, since they stay in tents or low cost infrastructure in refugee camps.”

The protagonist’s class consciousness is robust, a sense intensified by her journey up the social ladder. From an training in an American college to a migrant cleaner who flirts with intercourse work, apprehensive a few mom and sister who stay with few sources in an condominium in Istanbul.

The fable of Berlin, as a metropolis of alternatives

In The ApplicantLeyla and her pals cling to the parable of Berlin as the town of alternative the place, supposedly, initially of this century you would stay for a low lease and flourish artistically and socially. However, the social elevator is damaged, much more so in the event you come from a non-EU nation like Türkiye. “Our origin should not give us more human rights, but nationality and citizenship are concepts so ingrained since childhood that even the staunchest defender of human rights finds it difficult to think like this.”

In the midst of chaos and restlessness, the protagonist builds a construction: the “treasures of the day,” objects misplaced within the hostel that turn out to be hers (bottles of whiskey, the novel The great good friendby Elena Ferrante, a tracksuit…), her journeys on the U-bahn (Berlin metro), her events, her relationship with a loving “Swede” who she calls her antithesis (right-wing, with a great place at Volvo in Gothenburg ) and that makes her really feel like when she eats “her “mother’s” stew…

Humor and poetry come collectively in writing. The reminiscence of the nice style of tea is interspersed within the novel with “the stench of vomit, urine and poverty” of Berlin. “Irony works as a shield, it helps maintain sanity, even in difficult moments, such as during the demonstrations in Gezi Park in 2013 in Turkey,” which went from being protests over the conversion of that inexperienced house into a shopping mall to demand Erdogan’s resignation.

With a unadorned and biting prose, enlivened by ironic lashes and freed from drama, however filled with discoveries, The Applicant It is an invite to embrace life with every of its lights and shadows.

Babelia

The literary information analyzed by the perfect critics in our weekly e-newsletter

Receipt

https://elpais.com/cultura/2024-11-14/la-solicitante-un-diario-acido-sobre-una-escritora-que-limpia-habitaciones-para-subsistir-en-berlin.html