Inside a surprising week throughout Syria following the overthrow of the Assad regime | EUROtoday

Ghost cities emerge like bleached reefs flanking both sides of the lengthy highway north out of Damascus. Mile after mile of destruction glints by as if on a loop: such a widespread stage of devastation that it’s nearly unfathomable.

Empty, bombed-out cities, cities, and villages – as soon as bustling hubs of life – type the scars of 13 years of brutal and bloody civil warfare. Thirteen years of a pacesetter, Bashar al-Assad, attempting his hardest to bomb his inhabitants into submission.

This is matched solely by the economic scale of killing that went alongside it, in his prisons, intelligence branches, and torture rooms. The full extent of this horror is barely now starting to emerge, as dozens of mass graves are unearthed, because the lacking are counted because the lifeless, and because the chilling paperwork of a state that meticulously recorded nearly every little thing is prised out of submitting cupboards throughout the nation.

It is a scale of state homicide and torture of its individuals maybe unprecedented in our lifetime.

“The whole world should remember that the Syrian people suffered the worst crimes of the 21st century,” a Syrian army photographer and defector – codenamed Caesar – informed me in a uncommon interview from secretive exile simply after the beautiful overthrow of Assad.

The man, who has by no means revealed his true identification, spent two years within the early a part of the battle smuggling tens of hundreds of pictures in a foreign country. His job required him to doc the corpses of emaciated, tortured, disease-riddled detainees. These pictures turned important and harrowing proof of regime crimes that triggered among the hardest sanctions towards Assad.

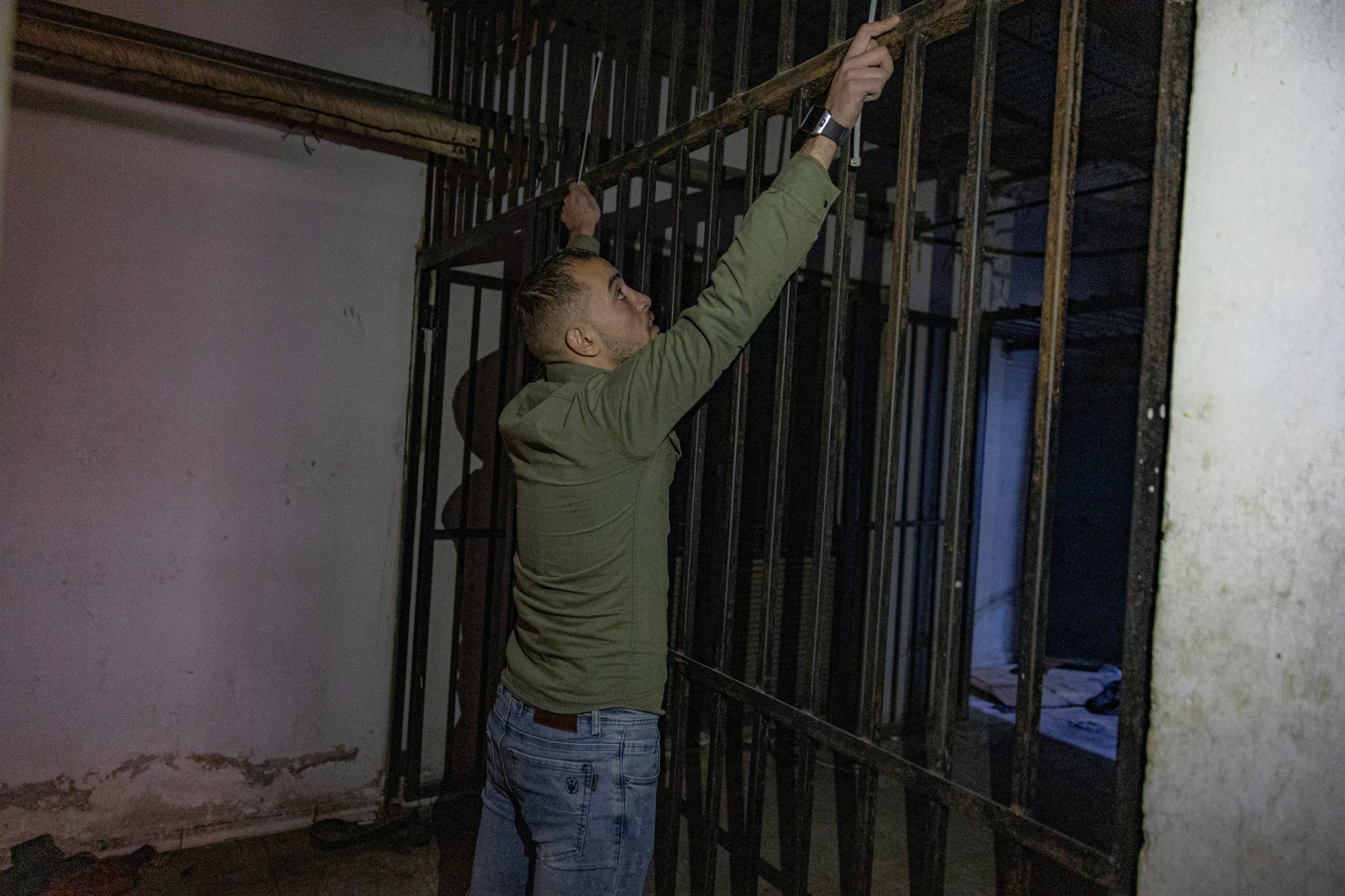

His declare that Syria has skilled among the worst crimes of the twenty first century may at first sound hyperbolic – till you too enter the morgues lined with mutilated stays of women and men, a few of their hole faces twisted in horror like The Scream. Until you, too, stand on the foot of mass graves, with canines sniffing out bones that attain out from the bottom. Until you, too, stand in sewage-soaked underground dungeons, studying the determined scrawls on the partitions of these swallowed for years inside windowless solitary confinement cells simply large enough to crouch in.

“I took almost 55,000 photographs of people who were tortured. And that was just in one place, in Damascus. It was just a snapshot in time, in geography, in place. But I can tell you this was going on everywhere else,” Caesar added. “And so, in terms of how many people have been literally tortured to death, it is in the hundreds and hundreds of thousands.”

The gravity of his phrases is mirrored by among the world’s most distinguished worldwide warfare crimes prosecutors, like Stephen J Rapp – a prime worldwide warfare crimes prosecutor and former US ambassador-at-large for warfare crimes points, who’s working with completely different organisations to doc the mass graves and determine officers implicated in warfare crimes.

The homicide and torture of the Syrian inhabitants was one thing “we really haven’t seen since the Nazis,” Rapp stated throughout a go to to Damascus this week. Speaking to me after visiting two newly found mass graves, he provides that Assad deployed a “machinery of death and state terror” over his personal individuals for many years and, crucially, documented it.

“It’s a regime that is document-mad,” he continued, baffled himself. Rapp has recognized practically 100 centres, from army intelligence branches to common prisons, containing substantial quantities of proof of those crimes – a paperwork so detailed and damning it was nearly “stupid”.

And that, he assures me, is the sunshine on the finish of the tunnel. There is an effective probability for some type of justice – if the proof, which proper now isn’t secured, will be preserved, and if the world helps Syria act shortly. But how did we get right here?

Before this December, Syria had largely been forgotten by the world. Initially, the 2011 revolution, which shortly morphed right into a bloody civil warfare, grabbed headlines – first by revolt, then bloodshed, and later by an unmatched refugee disaster that stretched throughout Europe, adopted by the arrival of Isis.

International superpowers scavenged over the chess items that emerged within the conflict-torn nation. Russia and Iran backed Assad politically and militarily, Turkey carved out a nook of affect within the northwest and the US guess on its chosen forces – the Kurdish-led factions within the northeast – towards its chosen enemy: Isis.

In the meantime, a complete era of Syrians was born into refugee camps, into exile, or into terror inside Syria, the place the economic killing machine labored its approach by the inhabitants. Some armed factions turned more and more radicalised.

Slowly, the nation started to turn into synonymous with warfare. Anything that occurred – irrespective of how geopolitical – was met with a shrug. War turned such an inevitability that it turned nearly an identification; many internalised the idea that nothing might or would change.

This numb resignation, mixed with home pursuits, even noticed Assad welcomed again into the fold: nations throughout the Middle East ultimately normalised relations with him and despatched ambassadors to Damascus. In May 2023, the Arab League voted to revive Syria’s membership. The peace dividends from this might possible be the ultimate nail within the revolution’s coffin.

But then December occurred. A hodgepodge of insurgent factions, led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a one-time al-Qaeda affiliate that has distanced itself from its jihadi previous, capitalised on a second in time. They efficiently stormed Aleppo, Hama, Homs, and eventually Damascus. Russia was embroiled in Ukraine, Iran-backed teams like Hezbollah had been reeling after a devastating battle with Israel, and the inhabitants of the nation was determined for change after years of warfare, disappearances, and financial hardship.

And so the actual fact we had been all in a position to cross into Syria – a rustic that had banned so many overseas journalists and left the overwhelming majority of us with “pending” visa functions for years – was weird. The feared checkpoints that severed the nation had been half-destroyed and empty. Regime uniforms had been swiftly discarded in clumps, and crashed armoured autos had been left deserted. Instead, two insurgent fighters from an unknown faction, sitting by a campfire with Kalashnikovs, waved us by.

The similar eeriness could possibly be felt on the websites of the once-feared regime prisons and bases. Such because the Republican Guard compound which seems to be down over Damascus, and was the headquarters of the dreaded commander General Bassam Al-Hassan, Assad’s adviser for strategic affairs, who was considered the important thing handler of Syria’s chemical weapons programme.

In the barracks, bowls of what appeared like half-eaten lentils lay discarded subsequent to washing traces of underwear and socks swaying within the breeze. The major workplace rooms had been trashed. Filing cupboards had been upended and a whole lot of IDs, passports, and papers had been scattered in all places.

“People are desperately looking for information about their missing detained relatives,” stated a guard, a insurgent fighter deployed to safe these buildings who declined to offer his identify.

“But I think regime people have also come to try to steal their files,” he added. Behind him, his comrades have caught a person rifling by drawers. Locals recognized him as an officer from the Assad stronghold of Latakia, a person who used to man checkpoints across the compound.

In the underground jail cells of the headquarters of the state safety constructing in Damascus, one other notorious detention centre, we encountered a group from Syria’s civil defence group, the White Helmets. They have introduced in a search-and-rescue canine unit to scour the premises for any signal of secret prisons.

When information broke that Assad had fled the nation and the jails had been thrown open, households descended on the primary prisons and detention centres of the capital, searching for family members. Some of them lacking for many years. For just a few feverish days, there was a perception that probably the most notorious jail, Saydnaya, simply outdoors the capital, may maintain a secret underground facility imprisoning hundreds who had by no means reappeared.

The White Helmets spent three days with former detainees and specialised search models, searching for any signal of life – however drew a clean.

“We still receive requests from people every day to find their relatives and so send teams and police dogs to every location to try to find them,” stated one White Helmets member in entrance of a line of solitary confinement cells too small to lie down in.

In one of many bigger cells, the wall is inexplicably coated with what seems to be an English language lesson with vocabulary starting from “chipmunk” to “heart attack”. Nearby, there’s a drawing of the quantity 107 London bus – a route that begins at Edgware Road. All clues as to who may need been there.

The group additionally pivoted to beginning the grim process of documenting any our bodies they discover in hospitals, morgues, prisons, and mass graves, that are solely simply being found.

At one mass grave in Qutayfah, 25 miles north of Damascus, the native inhabitants speaks of years of terror. It was operational between 2011 and 2017 – tens if not a whole lot of hundreds of our bodies could possibly be buried right here. “Anyone who dared ask questions about what was going on here was arrested,” stated one resident known as Alaa, 33, who says he was detained for greater than a 12 months for taking a single photograph of the positioning, when he noticed a canine pulling a human leg from the bottom.

HTS, probably the most highly effective of the insurgent teams, who’re largely accountable for this unusual transitional interval, are eager to maintain the peace – particularly round such delicate websites. They at the moment are guarded by insurgent fighters, lots of whom are being sculpted right into a civilian police power.

In Homs, Syria’s third-largest metropolis, which firstly of the civil warfare was nicknamed the “cradle of the revolution”, the brand new, HTS-installed police chief defined that they’re attempting to deal with the safety vacuum left by the beautiful, sudden finish of the dreaded intelligence and police community of the Assad regime.

Alaa Omran was Homs’ native authorities police commander till he witnessed the regime practically flatten the Baba Amr suburb of the town, which horrified him a lot that he joined an Islamist insurgent group. HTS ultimately recruited him to police a nook of the opposition-held northwest of Syria.

Like different police chiefs HTS has arrange in several elements of Syria, he has the inevitable process of attempting to keep up this tense, fragile calm. The major considerations are dropping management, revenge assaults towards anybody affiliated with the regime, assaults from regime parts themselves who’re hiding in plain sight, and investigating many years of regime crimes. As nicely as – and that is in all probability the most important ask of all – attempting to rehabilitate the picture of the police, who’ve been feared for half a century, all whereas successful over the opposite sections of society, together with Christians, Alawites – the spiritual sect that Assad belongs to – and Kurds.

“We plan to double our forces everywhere and improve the image of the police,” he informed me from his new desk, which, till only a week earlier than, had been occupied by the top of an Assad intelligence community.

How simply this can occur just isn’t clear, and within the Alawite neighbourhoods of the town, residents are nervous. HTS leaders have repeatedly insisted that they won’t impose spiritual restrictions on any group within the nation, but nobody has any thought if HTS will, for instance, implement hardline spiritual rule. They do not know how they are going to handle minority communities.

“We just don’t know what the new rules will be; that lack of clarity is unnerving,” stated one man.

This was echoed within the Christian neighbourhoods of Aleppo, the place anxious messages are despatched on daily basis saying that insurgent fighters from an unspecified faction have repeatedly turned up at their alcohol shops and requested them to shut. There had been protests in Damascus final week by teams demanding secular rule and the involvement of girls – the primary such rallies because the fall of Assad.

Down within the south, in Deraa, the place the 2011 revolution was ignited by a bunch of teenage boys impressed by uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia scribbling on the wall of their faculty, the sensation was, nonetheless, considered one of hope.

There, we chanced on Muawiyah Siyassna, a resident of Deraa who very a lot began, and in some methods completed, the revolution towards the hated Assad.

At simply 19, he wrote 4 phrases on a wall: “It’s your turn, doctor,” referencing Assad, a one-time eye physician: an act which obtained him arrested and detained for 45 days, sparking native protests that shortly unfold throughout the nation.

His story is the story of all of Syria: from abused youngster detainee to refugee in Turkey, he went on to combat with the Free Syrian Army, earlier than changing into disillusioned and smuggling himself again into regime-held territory the place he laid low. In early December, he picked up his Kalashnikov once more and ended up becoming a member of the primary wave of insurgent forces from the south who took Damascus from Assad.

Still holding his rifle and sitting within the courtyard of that Deraa faculty the place this story started greater than a decade in the past, he mourned the numerous family and friends members – together with his father – who had been consumed by the ferocity of the regime, whether or not on the battlefield or within the jail compounds.

For him and others of his micro-generation, youngsters when the revolution began, their grownup lives have been consumed by the heartbreak of autocratic rule, brutal civil warfare, displacement, and disappearances. Their future “is already lost” he stated.

But the work of rebuilding the nation, the compiling of war-crimes circumstances and bringing these accountable to justice might save his son’s future and the way forward for these to return.

“The future of the next generations is what matters,” he said. “I pray for them – that they won’t face the torture we faced, that they won’t have weapons, that they won’t live in the wars we did.”

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/syria-war-assad-hts-map-b2668706.html