Treasury sells remaining NatWest shares 17 years after bailout | EUROtoday

BBC

BBCThe Treasury has introduced the sale of its remaining shares within the NatWest Group. It means the financial institution might be below full non-public possession, virtually 20 years after it was bailed out by the taxpayer amid the 2008 monetary disaster.

This marks a symbolic finish to a dramatic chapter in British banking historical past.

It was gone midnight – the early hours of Monday 13 October 2008 – when Chancellor Alistair Darling turned in for the night time, leaving a workforce of officers, surrounded by curries and pizza bins, finalising the element of the most important state intervention within the non-public sector since World War Two.

The subsequent morning he introduced the primary instalment of a rescue that may price the taxpayer greater than your entire defence funds.

In whole the federal government spent £45bn (£73bn in at this time’s cash), shopping for an 84% stake within the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which now trades as a part of the NatWest Group.

Luke MacGregor/PA Wire

Luke MacGregor/PA WireAt the time, RBS’s stability sheet (excellent loans) was larger than your entire UK economic system. Its collapse would have devastated it.

The query is, why has it taken some 17 years for the Treasury to promote the final of its stake?

And provided that within the a long time since recent dangers have emerged – together with the specter of a cyber assault from a hostile state – how weak does that depart UK banks at this time? Are they nonetheless “too big to fail”, as they had been broadly described in 2008 – and had been Britain to face one other monetary disaster, would the taxpayer should step in as soon as once more to ship a bailout?

‘It was by no means about saving the banks’

The present chair of NatWest group, Rick Haythornthwaite, has advised the BBC that the financial institution and its staff stay grateful for that intervention in 2008.

“The main message to the taxpayer is one of deep gratitude,” he says. “They rescued this bank. They protected the millions of businesses and home-owners and savers.”

Quite a bit has modified since 2008. Gone are £1.5 trillion in excellent loans, gone are tens of hundreds of staff in job cuts, and gone is round £10bn of taxpayers’ cash – by no means to be recouped.

The quantity spent by the federal government seems to be like a poor funding, however as Baroness Shriti Vadera – former senior adviser to the federal government and chair of asset supervisor Prudential – advised the BBC, this wasn’t an funding, it was a rescue.

“Nationalising RBS was hardly a voluntary investment,” she says. “What was important then was assessing the impact of RBS and other banks on the overall economy and in particular the ability to keep functioning – lending, putting cash in ATMs.

“It was by no means about saving the banks, it was about saving the economic system from the banks.”

The consequences of a banking collapse would have been serious. The prime minister, Gordon Brown, even talked about putting soldiers on the streets.

In a book by ex-Labour spin doctor Damian McBride, Brown is quoted as saying: “If the banks are shutting their doorways, and the money factors aren’t working, and other people go to Tesco and their playing cards aren’t being accepted, the entire thing will simply explode.

“If you can’t buy food or petrol or medicine for your kids, people will just start breaking the windows and helping themselves.”

Risky mortgages and unhealthy loans

RBS was after all not the one financial institution that confronted collapse. A tsunami of unhealthy loans had been triggered by an earthquake within the US mortgage market. Risky loans to debtors with low credit score scores had been packaged up and offered to banks all over the world.

By 2007, no-one knew precisely the place these grenades had been hidden in financial institution stability sheets, so all of them stopped lending to one another – which noticed the entire world monetary system seize up.

Northern Rock relied on borrowing funds to finance its personal dangerous mortgages and in 2007, the BBC reported that it had turned to the Bank of England for assist. This prompted a “run on the bank”, which lastly noticed it totally nationalised in February 2008.

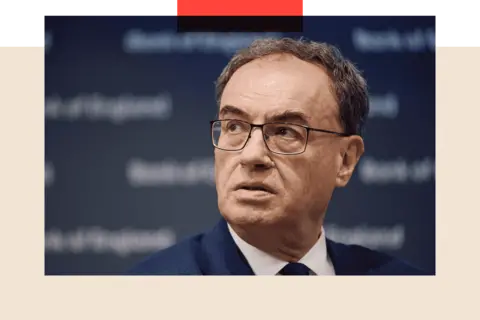

Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, labored because the Bank’s Chief Cashier throughout these turbulent months. He says if the state hadn’t nationalised RBS, the prices would have been “incalculable”.

“It would have been huge, because we were talking about the collapse of the banking system as we knew it at that time,” recounts Bailey.

Benjamin cream/ pa wire

Benjamin cream/ pa wireUS Banks had been additionally in deep misery. In March 2008, Bear Stearns was absorbed by Wall Street rival JP Morgan. In September of that 12 months, US mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had been nationalised. Here within the UK, HBOS was absorbed by Lloyds after which after all, Lehman Brothers failed – defying expectations that the US authorities would step in to put it aside.

But for the UK economic system, RBS was the massive one. The UK had a big banking sector, in comparison with the dimensions of its economic system; and inside that blend, RBS was a very necessary financial institution.

The as soon as sedate RBS had change into in some measure the most important financial institution on the planet. In 2000, it purchased NatWest and only a 12 months earlier than the crash, it had purchased Dutch financial institution ABN Amro.

Its buccaneering boss Fred Goodwin had been knighted for his companies to banking. But Mr Goodwin turned a lightning rod for public outrage on the dangers banks had taken and the bonuses their executives had collected.

He left with an annual pension of £700,000 however was later stripped of his knighthood.

Reuters

ReutersThe years following the rescue noticed hundreds of firms complain that the bankers RBS appointed to assist them out of the disaster had been driving them to the wall, forcing them into chapter 11 or promoting their companies at knock-down costs.

RBS was the poster baby for banking recklessness, hubris, greed and cruelty.

Why then did it take so lengthy for the federal government to promote out of RBS – at a lack of £10bn?

A mistake to carry on for therefore lengthy?

At the identical time the federal government took a stake in RBS, it additionally took a stake in Lloyds. But that was offered in May 2017, yielding a revenue of £900m.

RBS was infinitely extra difficult than Lloyds because it had a big US enterprise which was the topic of prolonged investigations by the US Department of Justice. The prospect of heavy fines hung over the financial institution for a few years and proved well-founded when it was fined $4.9bn (£3.6bn) in 2018 for its function within the US mortgage disaster.

RBS was additionally a reasonably unattractive funding. It introduced a £24bn loss for 2008 – the most important loss in UK company historical past. It made losses yearly till 2017.

With the shares depressed by these issues, the federal government was reluctant to promote its stake at low costs as it will crystallise a politically uncomfortable loss for the taxpayer.

Reuters

ReutersAfter all, following 2010, austerity was the secret and the then-Chancellor George Osborne might sick afford to be seen to be chalking up losses by promoting RBS shares when he was making cuts elsewhere.

But many assume that was a mistake as – rooster and egg-like – it extended the reluctance of personal shareholders to purchase stakes in an organization majority-owned by the federal government.

As Baroness Vadera places it: “I’m not sure it was necessary to take 17 years to reverse out of the shares.”

Collapses ‘much less probably – however not not possible’

Mr Haythornthwaite, who took on the function of NatWest Group chairman in April final 12 months, describes the sale of the ultimate shares as a “symbolic” second for the financial institution, its staff, traders – but in addition on a wider scale.

“I hope it’s a symbolic moment for our nation [too],” he says. “That we can put this behind us. It allows us to truly look to the future.”

But how precisely does that future look – and have classes from the previous actually been learnt?

Andrew Bailey actually thinks so. He says that if a financial institution faces collapse now, it is much less probably the taxpayer must step in.

There are actually different strategies of rescuing a failing financial institution, he says, together with shopping for belongings and offering emergency money.

“The big distinction is that we think we can handle [bank crises] without using public money,” Bailey says. “The critical thing is that we have to preserve the continuity of their activities, because they are critical to the economy … critical to people.

“When we are saying we have solved ‘too massive to fail’, to be exact, I feel what we imply is we do not want public cash.”

It is true that the Bank of England now stress-tests banks much more rigorously to see how they would cope under pressures like a collapse in house prices, rocketing unemployment or rampant inflation.

Sir Philip Augar, a veteran of the City of London and author of multiple books on banking, agrees that British banks are in a more resilient position now than they were in 2008 – essentially because they hold more cash in their coffers, rather than just relying on debt.

“What’s occurred to enhance issues since then is that the quantity of leverage within the system has come proper down, and the capital cushion that banks have to carry […] has elevated considerably. So it is much less probably now {that a} financial institution would collapse – nevertheless it’s not not possible.”

Cyber danger won’t ever go away

Today, there are also new risks to consider.

Take the series of cyber attacks that recently hit the systems of household names like Marks and Spencer, Co-op and Harrods. Should an attack take out critical banking functions like business lending, company payrolls and ATMs, it would be far more damaging.

Indeed, in what he calls the “league desk” of financial risks, Andrew Bailey identifies the threat of a cyber attack as a rapidly growing one.

“Of course you need to mitigate it, however [cyber] is a danger that can by no means go away, as a result of it regularly evolves,” he says.

“We’re coping with unhealthy actors who will regularly refine the traces of assault. And I all the time should say to establishments, ‘You’ve acquired to proceed to work at this’.”

Recent bank collapses in the US – like Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank – have highlighted another major risk. Customers don’t have to queue round a block to get their money out; it can be done with the stroke of a key on a laptop or mobile in seconds.

Banks are built on trust: customers put money in, believing they can get it out again whenever they want. And a good old-fashioned bank run is now a modern digital bank run.

But banks are still not like normal companies. They are not standalone entities but interconnected, and together they form the bloodstream of the economy.

They are the arteries through which credit is extended, wages are paid, savings are stashed or withdrawn. And when those arteries get blocked, bad things happen.

That is as true today as it was in 2008.

BBC InDepth is the house on the web site and app for the very best evaluation, with recent views that problem assumptions and deep reporting on the most important problems with the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content material from throughout BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can ship us your suggestions on the InDepth part by clicking on the button beneath.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cd0l4l4kpnko