After practically 40 years of paying taxes and elevating children in America, they’re self-deporting | EUROtoday

In the late Nineteen Eighties, after the US-backed Pinochet regime had destabilized their nation, José* and Claudia* moved from Chile to California with their two younger daughters. Alejandra*, the oldest, was 5 years outdated; Ines* was nonetheless an toddler, about to show one.

Their mom nonetheless has her outdated Chilean passport with the three-person photograph they took for the journey, Alejandra and Ines grinning collectively of their mom’s arms. Back then, minors routinely traveled on their mom’s passport.

Alejandra and Ines are lengthy grown now, each of their mid-30s. José and Claudia are each 65 years outdated. And as a substitute of doing what they at all times imagined they’d be doing — celebrating their naturalization, retiring comfortably after working and paying taxes diligently, attending to know their daughters’ new households — they’re planning a really totally different life.

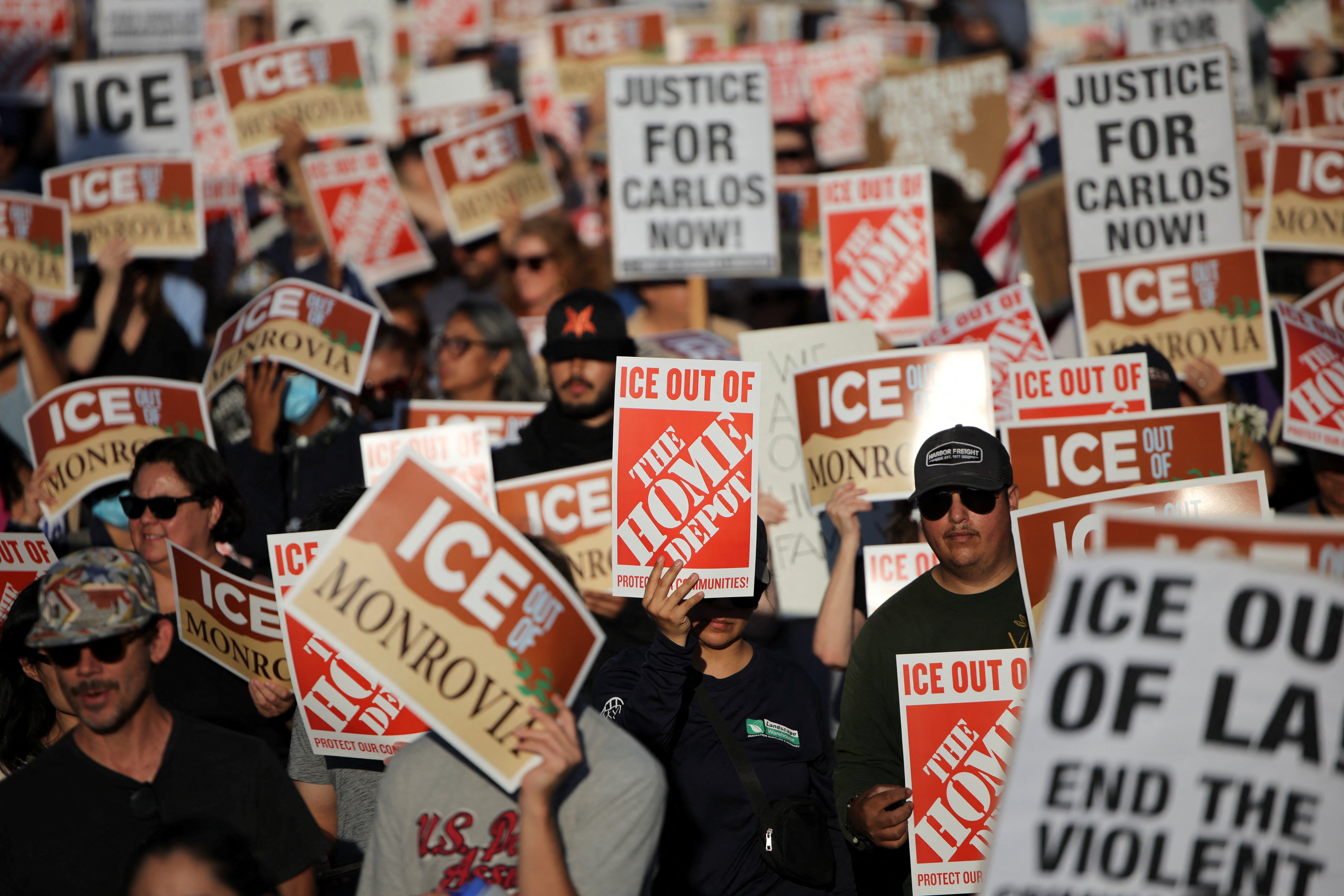

They are packing up virtually 40 years’ value of belongings, keeping track of the neighborhood apps that allow them know when ICE is within the space, and holding clandestine conferences with an immigration lawyer about the way to self-deport safely. After spending virtually their complete grownup lives in America, José and Claudia plan to kiss their daughter goodbye outdoors their rented household residence and get on a aircraft at LAX within the subsequent few weeks. They know they’ll by no means be allowed to return.

“The thing is, we were for so many years over here paying taxes,” says José. “And working hard, working so hard… We pay, pay, pay, and we receive nothing back. And the worst thing is [Claudia] got sick, and I got sick.”

Undocumented immigrants throughout the US have lengthy paid taxes, even with out authorized immigration standing. Since 1989, the IRS has allowed folks with out Social Security numbers to pay earnings taxes by utilizing an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN).

This system was created so anybody incomes cash within the nation might meet their tax obligations, no matter immigration standing. Many undocumented employees even have taxes withheld robotically from their paychecks by employers, that means they contribute to federal applications like Social Security and Medicare although they don’t seem to be eligible to gather these advantages.

That means undocumented folks have been steadily contributing to America’s tax base for many years — an estimated $96.7 billion in 2022 (the newest 12 months on file) alone, based on the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. That consists of nicely over $8 billion within the state of California, the place José and Claudia have at all times lived.

Although their life in California wasn’t as laborious as their scenario in Chile — the place tens of 1000’s of socialists had been murdered below the fascist dictatorship, and unemployment had reached virtually 30% — it was nonetheless a troublesome life for José, Claudia and their two younger youngsters.

Ines remembers their preliminary condo within the Coachella Valley with fondness: “We had a lot of community back then,” she says. “Our neighbors were our friends, like in the apartment complex, and everyone was Latino. There were Chileans, Peruvians, Mexicans, a lot of Cubans. Growing up, there were just so many immigrants around us, actually.”

They had a supportive group nevertheless it was very totally different from Chile. José and Claudia struggled to adapt to the desert setting, the place summer time temperatures often topped out at 120F (“I mean, Chile is a cold country!” says José.) And they realized English slower than their youngsters, who turned fluent as soon as they went to high school.

While Ines and Alejandra progressed by way of elementary, center and highschool, José labored putting in water filtration methods and Claudia waited tables in eating places. And slowly, the immigration legal guidelines modified for the more serious. First to go, in 1993 below the Clinton presidency, was the flexibility for undocumented immigrants to carry full and unrestricted drivers’ licenses. That meant that though José and Claudia might maintain renewing the licenses they’d utilized for below the Reagan administration, their youngsters wouldn’t have the identical privileges.

“I think it was really hard for me and my sister when we were teens, and we realized that there was a lot we couldn’t do,” says Ines. “Our school would be going on a trip and we’d be like: Oh, we can’t do that. Or I’d want to get a driver’s license and I can’t at 16… And they’re these really big markers of liberation when you’re young, of being like, ‘I’m gonna drive!’ or ‘I’m gonna get on a plane for the first time!’ And we were like: Oh, we can’t do those things.”

Where they lived was a seasonal city, and their mother’s wages particularly had been depending on vacationers. Six to eight months of the 12 months, the household could be doing OK. And then funds would all of a sudden drop, and there was no security internet. At one level, when Ines was in highschool, the household needed to transfer right into a small home with “a bunch of other immigrants”. She remembers there being 10 folks in a tiny, cramped house, dwelling virtually on high of one another.

“We had a lot of curiosity, both my sister and I, about where we were from,” Ines provides. “We wanted to understand and feel a part of the place that we were born in.” But they couldn’t journey again to Chile: “Going back meant that we could never come back to the States. And we knew that.” Indeed, any worldwide journey in any respect was off the playing cards. For Ines particularly, who entered the US as a child and had no reminiscences of wherever else, the concept she may very well be barred from America felt each terrifying and absurd. So she accepted that she’d have to remain put.

Both José and Claudia have medical situations that require each day medicine: José has diabetes and Claudia has rheumatoid arthritis. They’ve spent the previous few years self-funding their healthcare by way of Obamacare, however now they’ve turned 65, they’ve aged out. American residents of their scenario would begin Medicare (or the California equal, Medi-Cal.) But, as a result of they’re undocumented, they don’t qualify. They’ve paid taxes towards the system all their lives, however they gained’t be capable to entry it themselves. And paying out-of-pocket medical bills merely isn’t sustainable.

As the top of the Biden presidency approached, Ines hustled to get her inexperienced card and citizenship sorted as quickly as doable. She’d simply married an American citizen — and she or he’d entered the US as a toddler, making her a DACA recipient or “Dreamer” — so she nonetheless had a straightforward route. It was nonetheless costly and time-consuming, and drained her paltry financial savings. But she did it, with the hope that she’d be capable to sponsor her dad and mom to turn into residents not lengthy after.

Then Trump’s second time period started, and the results had been a lot worse than they’d all imagined. José and Claudia stopped going out as a lot. They checked the apps each time they wished to seize milk from the shop.

And then experiences began coming in of individuals attending their authorized, organized appointments with ICE and USCIS and being arrested. People had been being taken into custody at inexperienced card interviews or once they went to attend immigration courtroom. American residents had been being jailed and held in ICE immigration raids in California. No one appeared to be immune: a 71-year-old girl was handcuffed by ICE brokers in San Diego at a courtroom listening to; a pregnant girl was allegedly wrongly arrested and assaulted by ICE officers, inflicting her to enter early labor; a whole bunch of undocumented Venezuelan migrants had been arrested, placed on planes, and transferred to the El Salvadorian mega-prison CECOT, regardless of the overwhelming majority of them by no means having dedicated a criminal offense.

“The most scary thing is, if something happened to us — if they arrest us or something — we can die,” says Claudia, “because [José] is diabetic. They don’t care. They don’t care if you have medicine or not. They don’t tell you where you’re going… They just arrest and keep you. That makes us very, very scared. My husband and I, we are scared.”

The household has now determined it isn’t well worth the threat to even apply for José and Claudia’s citizenship. A courtroom date or an interview with ICE isn’t value dying for. Instead, they’ve determined to maneuver to a 3rd nation, which they don’t wish to disclose publicly. But even flying in another country from a California airport comes with its dangers, so that they’ve spent their remaining funds on using an immigration lawyer to escort them onto the aircraft and intervene if something occurs. Every step of the best way is paved with concern.

“One of the things that we talked about when we started making this decision was that my dad, for the first time ever, was monitoring how much my mom could leave the house,” says Ines. “And he himself was like: I’m not gonna leave the house much at all anymore.” A few weeks in the past, the couple had a minor falling-out earlier than Claudia — who now drives taxis for a dwelling — went to work. She switched her cellphone off for an hour, and when José rang the taxi agency to verify in on her, they talked about that she hadn’t been seen for a pair hours since she dropped off somebody in an immigrant-heavy neighborhood identified for latest ICE raids. José referred to as Ines, who tried to contact her mom and couldn’t. They drove to the taxi agency’s headquarters collectively, Ines sobbing, satisfied she may by no means see her mom once more.

“I was bawling, crying,” says Ines. She begins to cry once more as she remembers the concern that she and her father felt. “I was like: How do I find out where she is? And I realized in that moment, there’s no way to know where they took her. If they just take your family member, I was just like: How the hell do I find out? I need to be able to call a place or a number or something, or someone, to be like: Where’s my mother?”

Eventually, Claudia returned to the agency’s headquarters from her newest journey, protected and sound. José and Ines ran as much as her, saying, “You can’t do this to us again — we thought you were kidnapped.” Ines describes it as “one of the scariest moments I’ve had in a long time.” Somehow, over the previous few weeks, this has turn into their actuality. “And I think sometimes it feels like it’s not or something — we can live day to day and we laugh and, you know, we’re still people,” she provides. “We go to the store and we have our jokes. We hang out. It was my birthday yesterday, so we celebrated together. And we have so many moments of joy, but the reality that we’re living under is like, if we can’t reach my mom for an hour, we think that someone’s literally going to kill her because she’s an immigrant.”

It’s a tragic strategy to dwell out your golden years, says José: “We gave so much to this country. We worked very hard all our life here… So it’s not fair for us to live with this fear. Every day we watch the news and it’s just the same things, negative things. Poison things.”

It will probably be troublesome to go away America. José says that he loves the nation; that he’ll miss their block, their associates, the neighborhood the place they raised their youngsters. But now Alejandra has left along with her husband to dwell in Greece, tired of staying in a rustic so alive with anti-immigrant fervor. And Ines is staying in Los Angeles for now, however she imagines she’ll quickly observe her dad and mom. “I just need a moment,” she says, “before I leave my life behind. I’m like: I will go meet you, I just need a second.”

Between the 2 sisters, they’ve saved up sufficient cash to pay for his or her dad and mom to dwell for a 12 months and get settled of their new nation. After that, the longer term stays not sure. José and Claudia personal no property. The furnishings they’ve will probably be donated to different relations who’re arriving within the U.S. What they’ll promote to go towards their dwelling bills, they’ll over the following couple weeks. They will arrive at their new residence — by way of a “very specific route” that they’ve labored out with the lawyer, one which’s much less more likely to get them flagged by ICE on the airport — with “seven or eight suitcases,” all that’s left of their time in United States. A pal of the household, primarily based elsewhere within the state, is working a GoFundMe to cowl a few of their bills.

“You fall love with a country,” says José. “For so many years, we were over here. And it’s difficult to say goodbye to everything, the street, you know, everything. And to start thinking about another culture at this age — it’s hard. We try to be positive.”

“I feel so protective of them,” says Ines. “And so I put on a really strong front. But the truth is that we were displaced in actually a big way because of a US-funded coup in our country. And things got really hard in Chile, and we came here literally because of US dollars and US intervention in our politics and to be pushed out this way… I’m just angry.” She thinks of what her dad and mom went by way of, figuring out that they had been making a choice that might possible imply they’d by no means see their residence nation once more, figuring out that they had been giving up a whole lot of their freedoms with the intention to construct a greater life for his or her youngsters. The future they imagined, once they crossed the border in 1989, was so totally different.

If they’d identified that this was the route America was headed in once they crossed the border 36 years in the past, I ask José and Claudia, would they’ve made the identical choice? Both of them reply instantly: “No.” They by no means would have come to the United States in the event that they’d have identified. They would have left Chile, however they’d have immigrated some place else.

There is a way of empowerment in selecting to go away, says Ines: “It’s just like: No more, you can’t terrorize us anymore. We’ve already been living in fear.” Pre-DACA, “it was so scary for me,” she provides. “I was undocumented. It was horrible. It was super xenophobic here. Cops used to just stop us because of profiling, it happened to us many times. And my dad saved me once from a cop, because I didn’t have any identification. My dad lied and said I was younger than I was.” And as of late, “it’s so much scarier… Now there’s no pretending. It’s so open: ‘We want you dead.’ It’s so clear, it’s so racist, it’s so xenophobic… So it does feel somewhat empowering for us to say: No, we’re choosing a different life.”

There are some small however necessary positives. For virtually 4 a long time, José and Claudia saved their heads down, labored and grinded, didn’t let themselves take into consideration the longer term past the day-to-day. But as soon as they go away the U.S., “they’re not trapped anymore,” says Ines. They’re going to be free to journey the world. “My dad was just saying he’s going to take my mom to Italy to see this bridge that he always wanted to, since they met over 40 years ago.”

“Living with the stress every day is not good enough for us,” says José. “It’s not good. No, no way. No, I’m tired.” He is aware of that the longer term gained’t be straightforward. He is aware of issues didn’t work out how they deliberate. He is aware of that even the exit route is mired with doable hazard. But it is going to be good, he says with a smile, to “be free”.

The names of José, Claudia, Alejandro and Ines have been modified to guard their identities. A GoFundMe is being run for the bills surrounding their self-deportation, which you may contribute to right here

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/self-deporting-ice-california-b2816141.html