Leonardo’s world map | Science | EUROtoday

The space of final week’s Reuleaux triangle (R) is the same as that of the equilateral triangle with aspect 1 (T) plus thrice the world of the round phase (S) on both sides:

R = T + 3S, the place S is the round sector minus the triangle:

S = π/6 – T, then

R = T + 3(π/6 – T) = π/2 – 2T

T = √3/4

R = (π – √3)/2

Some readers have identified that there are additionally cash formed like Reuleaux polygons. The finest recognized is unquestionably the British 50 pence coin, which is a Reuleaux heptagon.

The reply to the query of whether or not there may be Reuleaux polygons (that’s, of fixed width) constructed from some irregular polygons or with a fair variety of sides, posed final week, is affirmative; however on this case the arcs of the ensuing polygon is not going to all be equal or with the identical curvature.

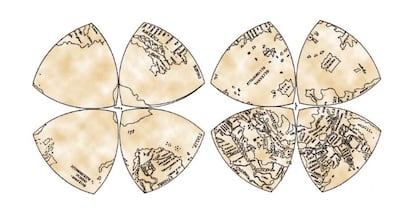

The octant projection

One of the least recognized, however no much less essential, points of Leonardo da Vinci’s actions are his contributions to cartography. In his miscellaneous Codex Atlanticuspreserved within the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, there’s a manuscript from 1508 through which Leonardo analyzes the various kinds of cartographic projection recognized at the moment, comparable to Ptolemy’s flat conical projection or Contarini-Rosselli’s planisphere, and introduces a brand new one, which consists of dividing the globe into eight octants after which flattening them into the form of Reuleaux triangles. Was this an arbitrary or purely aesthetic selection, or does the flattening of a sphere octant essentially produce a Reuleaux triangle?

Leonardo grouped the 4 octants of every hemisphere forming a sort of four-leaf clover, with the poles within the respective facilities of every clover, giving rise to what’s often called “Leonardo’s World Map”, though its authorship shouldn’t be sure (some suppose that it was drawn later by one in all his assistants); however what’s solidly demonstrated is that the Renaissance genius was the primary to suggest the projection in octants and their grouping in two four-leaf clovers, as attested, amongst different issues, by a sketch of the aforementioned manuscript of 1508 included within the Codex Atlanticus.

It ought to be famous that the projection in octants is neither conformal nor of equal space. In cartography, a conformal projection is one which preserves the angles (or at the very least most of them), such because the Mercator projection or the stereographic projection, and an equal space projection is one which preserves the proportion of the surfaces of the completely different nations or different geographic areas represented. Other traits that could be handy to protect, relying on the kind of map you want to make, are the form of the completely different geographical areas, distances, instructions…, and generally preserving one in all these variables means distorting others. Can a cartographic projection be each conformal and of equal space? As?

And, to complete, I ask my sagacious readers a query that, though it could appear botanical, is pure logic: Are there four-leaf clovers?

https://elpais.com/ciencia/2025-10-31/el-mapamundi-de-leonardo.html