The writer and columnist finishes ‘The newspaper of democracy’, his explicit imaginative and prescient of the medium and what it has meant in his life to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of its look: Javier Cercas finishes ‘The newspaper of democracy’, a guide about EL PAÍS | Culture | EUROtoday

In the nineties, Javier Cercas (Ibahernando, Cáceres, 63 years outdated) didn’t enable himself the posh of dreaming that sooner or later he would make a dwelling from literature when an anecdote between hooligan and Cervantes ruined one in all his days as a college professor in Girona. He acquired a name from a stranger who requested him if he want to write for EL PAÍS. That is, for him, at that second, not simply any newspaper, however the one he had at all times learn, the place everybody needed to write down, probably the most related within the Spanish language, the identical one which stood as much as the coup of 23-F, that of García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Pradera, Rosa Montero, Umbral, Vicent, Savater… “I went from disbelief to euphoria in seconds,” he remembers. He hung up and the telephone instantly rang once more. It was her sister Sofía: “Do you know who just called me?” she requested. “Of course I know, idiot. Do you know what day it is…?” The calendar turned out to be merciless and destroyed his dream: December 28, the day of the Holy Innocents.

His sister performed a prank on him, however it could show premonitory. Years later, after a literary—and alcoholic—disquisition amongst mates about who had dared to shut a novel with the phrase shit, simply as he had executed in his third work, The stomach of the whale, Agustí Fancelli, exuberant and music-loving author for EL PAÍS in Catalonia, advised him: “And you? Why don’t you write chronicles?” That time it was actual and Cercas received to it earlier than leaping into The Weekly Country by the hand of Álex Martínez Roig. And there he’s nonetheless, three a long time later, stoking and reflecting twice a month on 4,200 characters.

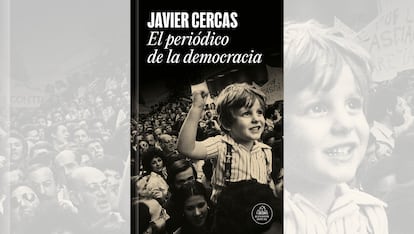

They are parallel traces of life that Cercas has witnessed in The newspaper of democracy (a private story from El País) (Random House), the work with which the writer of Soldiers of Salamis celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the medium’s look and can seem on Sunday, May 3 in newsstands and May 7 in bookstores. A title chosen on the premise of absolute forcefulness: “It is like this, unquestionable, among other things because it is born, as Manuel Vicent points out, free of original sin.”

It will likely be May 4 when EL PAÍS turns 50 years outdated. Five a long time whose celebration will likely be accompanied by nice fanfare, high-quality editorial initiatives and occasions open to the general public, which have already begun with Bill Gates’ convention final January on the Prado Museum. The spotlight will likely be a small competition in Matadero Madrid in the course of the first days of May.

“When I proposed this project to Javier Cercas, we agreed that it would not be a historian’s text, but rather the story of a reader. Of Cercas as a reader. The reason is that the history of EL PAÍS is also that of its readers. They are the recipients of that collective effort that is a newspaper. And this wonderful book is, in a way, a tribute to them and our shared history,” says EL PAÍS director, Jan Martínez Ahrens.

It appeared on May 4, 1976, six months after the dictator’s dying, one thing that, as had not occurred to different media in circulation, had freed him from reward on the day of his dying. EL PAÍS was enlightened by democracy, it contributed to forging it with a mass of essential readers and an infinite weight of affect after its dazzling success, roughly acrobatic, triple somersault, studied as an distinctive case within the press all over the world. It took simply two years to turn out to be the nationwide reference medium and probably the most learn. “Today it is global, in the context of Spanish throughout the world,” says Cercas.

It was concocted with a community of editors and intellectuals who sought a reform of the regime, between liberal and pro-European, for which there was no scarcity of figures from the regime with the ambition to guide the post-Franco regime, akin to José María de Areilza and Manuel Fraga. But inside the shareholders, those that had been in search of one thing extra quickly prevailed, akin to Jesús de Polanco, who together with others akin to José Ortega Spottorno, son of Ortega y Gasset, prevailed within the venture.

Juan Luis Cebrián was named its first director on the age of 31, who has been adopted by Joaquín Estefanía, Jesús Ceberio, Javier Moreno, Antonio Caño, Soledad Gallego Díaz, Pepa Bueno and at present Jan Martínez Ahrens. “Soon, Polanco and he reached an agreement where neither one nor the other should interfere and it turned out to be key.” For the editor, management of the corporate and its financial viability. For Cebrián, the Editorial Team. “And in this last case, setting an example, providing itself from the beginning with amazing democratic mechanisms, which did not exist in any newspaper and today, in many, still do not exist, such as the editorial committee, a control body in turn of the management itself,” says Cercas.

Cercas tells of the beginning of that compact drive, key within the development of democracy. “Although there were conservative elements in the shareholders, the editorial staff was made up of wayward, rebellious, progressive, left-wing journalists for the most part, and that was decisive for the success and influence of the newspaper in a society that sought to break with the previous.”

This is how what the thinker José Luis Aranguren outlined because the collective mental was additionally solid. A task by which Javier Pradera, its first opinion chief, was key: “He became the gray eminence of the Transition, its hard drive, as Felipe González described it.” Not solely within the political sphere. Also within the cultural. So a lot in order that opponents despaired of the medium’s affect and talent to raise and switch lots of the voices and creations of the brand new democracy into successes. “Luis María Anson defined it as a cultural custom,” says Cercas, particularly at a time when carrying a replica beneath your arm mechanically outlined you.

The writer highlights within the guide probably the most epic episodes, such because the night time of February 23, one thing that he has investigated intimately for his work. Anatomy of a second. When doubts prevailed and going out on the road posed an apparent threat that night time, Cebrián went right down to the editorial workplace in his shirt sleeves and mentioned: “Everything is clear here: there is a coup d’état and we are going to publish the newspaper.” The resolution was imposed after having reached a conclusion that left no room for doubt. They needed to behave like what they had been, journalists, and print it earlier than troopers arrived to occupy the headquarters at Miguel Yuste 40.

At ten at night time a particular version appeared with simply 16 pages: “Coup d’état. EL PAÍS with the Constitution.” Schematic, agency, an ax blow in writing to the revolt of arms. “Resisting the coup was contributing to aborting it,” writes Cercas. When it was in a position to be distributed and even reached Congress, that turned an apparent signal of failure, particularly when many noticed the civil guards, together with the colonel who led them, Tejero, with copies of their fingers.

All that’s History. Proven information. And we should concentrate on this in a future devastated by lies and a journalism that, within the area of significant and reference media, the writer assures, “it is no longer enough for the newspaper to tell the truth, it must also dismantle lies.” In this context of tips, political tales and demonized velocity races by way of social networks, Cercas believes that journalists and those that write within the medium should take note, he affirms, “their commitment to the truth, even if it harms their ideas, and that lies have been the best ally of national populism,” as he defines the present wave of authoritarianism.

Also that, above all, a newspaper has no which means whether it is only a enterprise. “That behind it, sustaining it and propelling it, there must be a moral and political project.” But, above all, a rabid, pragmatic and unwavering vocation for independence in protection and fixed dedication to freedoms, as occurred with EL PAÍS because the day it appeared half a century in the past.

https://elpais.com/cultura/2026-02-15/javier-cercas-escritor-ya-no-basta-con-que-el-periodico-cuente-la-verdad-ademas-debe-desmontar-mentiras.html