The Mexican author Carlos Fuentes tells in The nice Latin American novel a gathering he had with Mario Vargas Llosa in London in 1967. The assembly led to the thought of inviting a dozen Latin American authors to put in writing concerning the inexhaustible gallery of caudillos within the area and to compile the texts in a single quantity, The fathers of the homelandsThe challenge didn’t prosper, however it did result in the launch of a number of books within the Seventies that includes despotic historic presidents, a style that critics dubbed the “dictator novel”: I the supreme by Augusto Roa Bastos, The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, The useful resource of the tactic by Alejo Carpentier, Office of the Dead by Arturo Uslar Pietri… The twenty first century arrived and the democracies born after the autumn of authoritarian regimes proved to be weak: heads of state exchanged their army uniforms for shirts and ties, however the nature of autocratic energy remained intact.

Recent publications resembling The lives of JM by Martín Caparrós, The days of Kirchner by Fito Paez, Memoirs of a son of a bitch by Fernando Vallejo, Tongolele doesn't know methods to dance by Sergio Ramirez, Homeland or demise by Alberto Barrera Tyszka, Hard instances by Mario Vargas Llosa or I used to be by no means a primary woman Wendy Guerra's works counsel a renewal of this literary style. Absolutist leaders are now not the primary characters, however are portrayed via the outline of the societies they’ve constructed or the nameless individuals who encompass them.

Venezuelan Hugo Chávez, Nicaraguan Daniel Ortega, Cuban Fidel Castro and Argentine Javier Milei wander via the pages of those books. They are normally those who pull the strings with which the protagonists transfer. The necessary factor right here is to indicate the results they’ve left within the nations the place they proclaimed themselves as messianic champions. “We are facing a new phenomenon, and that is that before dictators came to power through violent coups d'état, and now they have the legitimacy of the vote. People elected Milei and Bolsonaro, also Bukele, Maduro and Ortega, but the latter believe that they will be presidents forever. These novels show the effects of their governments on society: repression, corruption, exile, but they do not address the figure as such. It is another branch of the dictatorship novel,” displays Nicaraguan author Sergio Ramírez.

Ramírez—who was vice chairman of Daniel Ortega from 1985 to 1990 earlier than turning into a persecuted dissident—depicts a rustic held hostage by the Sandinista revolutionary chief and his spouse, Rosario Murillo, in Tongolele doesn't know methods to dance (Alfaguara, 2021). The guide recounts the 2018 protests within the Central American nation, led primarily by college students, towards a reform of the social safety system that decreased pensions. The repression by the Army and shock teams was brutal and left greater than 300 lifeless and 1000’s extra tortured.

Another nation damaged by political disaster and polarization is evoked in Homeland or demise (Tusquets, 2015), by the Venezuelan Alberto Barrera Tyszka, who narrates the final days of Hugo Chávez's life. While in I used to be by no means a primary woman (Alfaguara, 2017), Wendy Guerra portrays the era of daughters of the Cuban Revolution, helpless and rocking in a stranded utopia within the middle of the Caribbean.

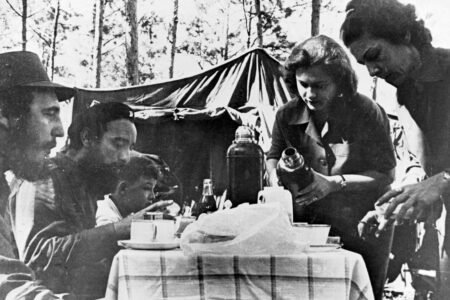

Carlos Herrera (image alliance / Getty)

The days of Kirchner (Emecé, 2018), the third guide by musician Fito Páez, doesn’t embody, regardless of its title, any look by former Argentine presidents Néstor Kirchner and his spouse Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. What is described is how Kirchnerism formed a progressive thoughts in Argentines, primarily in younger folks, in the course of the time they ruled (2003-2015). The protagonist embodies this ideology: “La China was a hopeful young woman who believed that the world had the possibility of being changed under the invisible laws of the search for the common good.” The counterweight on the size is supplied by her boyfriend, El Mono, a Peronist who shouldn’t be completely satisfied by the Kirchners’ one-way insurance policies, whom he accuses of clientelism and corruption: “Try to know who you are before you go around the world evangelizing idiots. Drown in some doubt sometimes,” he says in one of many elements of the guide.

“Each of these texts adapts the tradition of the dictator novel to its own poetics. They have understood that power is no longer exercised alone through a single man, but through an entire oppressive system that transcends these figures. Younger writers are making other kinds of books, also very political in other senses, but far removed from the patterns of boom novels,” says Jesús Cano Reyes, professor and researcher of Latin American Literature on the Complutense University of Madrid. Although fictionalizing dictators grew to become fashionable within the second half of the twentieth century, the custom of fictionalizing these tales goes again a lot additional in America, to the nineteenth century.

The novel Amalia (1851), by José Mármol, and the story The slaughterhouse (1871), by Esteban Echeverría, targeted on the determine of Juan Manuel de Rosas, governor of Buenos Aires and creator of the parapolice pressure La Mazorca. Then got here Tyrant Flags (1926), by the Spanish Valle-Inclán, thought-about by specialists to be an necessary affect on this subgenre. Saint Evita (Alfaguara, 1995) concerning the influential Argentine first woman Eva Perón, by Tomás Eloy Martínez or The Feast of the Goat (Alfaguara, 2000) by Mario Vargas Llosa, concerning the Dominican dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, supplied new approaches.

The indisputable fact that they contain actual folks doesn’t imply that they’re novels documented intimately, as defined by Paola Celi, a professor of Language and Literature on the University of Piura (Peru): “The historical aspect of these novels does not interrupt the aesthetic flow, but, on the contrary, enriches it.” The useful resource of the tactic (Cátedra, 1978), the Cuban Alejo Carpentier invents a protagonist composed of the Venezuelan dictator Guzmán Blanco and the Guatemalan president Manuel Estrada Cabrera to recreate the determine of the enlightened despot who, the day after listening to opera in Paris, crushes fashionable uprisings. This fusion between fiction and actuality can also be utilized by Martín Caparrós in his first digital and interactive novel, The lives of JM (Anfibia Magazine, 2024). Caparrós creates a fictional character, Julio Méndez, to satirize the Argentine president Javier Milei, who defines himself as an “anarcho-capitalist.” He attracts on actual occasions from the protagonist’s childhood to clarify his “resentful and furious” character, as the author and journalist explains.

“I don't know if there is a new formula [de la novela del dictador]but there is certainly a new type of rulers who are much more ridiculous than dramatic. So, it is logical that the way of approaching them also changes and is not tragic, but farcical,” says Caparrós. In that parodic tone, fluctuating between facts and imagination, is situated Memoirs of a son of a bitch (Alfaguara, 2019), by Colombian Fernando Vallejo. Written in the first person, in the form of a diatribe, it portrays a fictitious president, successor of Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (2010-2018), whom he claims to have shot alongside Álvaro Uribe, César Gaviria and Andrés Pastrana.

The Colombian's text is the one that comes closest to the classic style of dictator novels, by drawing a detailed portrait of an extravagant character, delving into his authoritarian motivations and contradictions. “These rulers who are intended to be criticized end up being, after so many pages, endearing or beloved by the writer and the reader. Frequently, there is a fascination for this type of megalomaniac characters around whom a mythical halo is created,” says Professor Cano.

The personality of these high-sounding speakers is usually captured from the perspective of other characters, as happens in Homeland or death. The protagonist, Miguel Sanabria, torn between the anti-Chavez extremism of his wife and the Bolivarian radicalism of his brother, says about Chavez, who gave a nine-hour lecture in 2012: “He was above all a sensation, the origin of the charisma that depended on the effusiveness of the masses. The cancer did not seem to affect his pride, his fascination with himself. On the contrary, he seemed increasingly convinced of his own greatness (…) His great triumph was to have consolidated his voice as the axis of society. He had created the talking State. Everyone repeated the words of the Messiah. It was a perfect structure because it was a voluntary and joyful exercise of submission.”

The identical train of reconstructing populist leaders via the eyes of different characters seems in I used to be by no means a primary woman. Wendy Guerra tells via her alter ego, Nadia, the daughter of Cuban guerrillas, talks about how since childhood she noticed the heroes of the revolution—the Castros, Che, Camilo Cienfuegos—as omnipresent deities. “All my life I have gone to bed and woken up listening to some speech. I cannot forget the voice that haunts me,” she writes within the guide. The work narrates the disillusionment of Nadia, who shouldn’t be certain she lives within the “same Free Territory of America for which they fought, that country in their heads was a wonderful place.” The different pillars of the novel are her mom, Albis, and Celia Sánchez Rey, the latter secretary and supposed lover of Fidel, essential within the overthrow of Batista in 1959. “It is a story of disillusionment, pain and loss. Today there are many Cuban women imprisoned for protesting in a country where the revolution asked you to revolutionize everything, it was the order,” she tells THE COUNTRY the author.

Why is the historical past of Latin America marked by those that cling angrily to the throne? Ramírez suggests: “In Latin America there has never been a crystallization of institutions that is capable of resisting the weight of tyrants, who when they sit on top, crack them. Look at the time it took Bukele to take over all the institutions; in less than a year he already had control of the Assembly, the judges of the Supreme Court, the Prosecutor's Office, the Police, the Army. This is what has happened in Nicaragua, but in the very long term. The institutions are weak and cannot withstand pressure.” Too many temptations.

All the tradition that goes with you awaits you right here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The newest literary releases analysed by the most effective critics in our weekly publication

RECEIVE IT

https://elpais.com/cultura/2024-09-14/de-los-regimenes-militares-al-chavismo-la-tradicion-de-la-novela-sobre-dictadores-latinoamericanos-se-renueva.html