Ohne diese Töne geht es nicht: Menschheitspathos muss sein, wenn Ludwig van Beethoven gefeiert wird. Das Bonner Beethoven-Haus hat das Autograph des 4. Satzes von Beethovens Streichquartett op. 130 erworben und zeigte es vorgestern geladenen Gästen. Der Geiger Daniel Hope, der beim Beethoven-Haus als Präsident, additionally oberster Spendenwerber, firmiert, sagte in seiner Begrüßungsansprache im Kammermusiksaal neben dem Geburtshaus, Beethoven habe „seiner Kunst eine politische, eine moralische und eine humane Dimension“ gegeben: „Wir blicken in Abgründe der Menschheit.“

Markus Hilgert, Generalsekretär der Kulturstiftung der Länder, die an der Spitze des Konsortiums öffentlicher und privater Geldgeber steht, das den Ankauf möglich gemacht hat, nannte die neun Blätter mit fünfzehn Seiten Notentext „ein Stück Menschheitsgeschichte“, das „auch künftige Generationen“ inspirieren werde. Ob die Menschheit am Ende durch Partiturstudium aus ihren Abgründen wieder herausfindet?

Man muss ihn einen Unmenschen nennen

Der Komponist Jörg Widmann hatte mit dem Festvortrag die Aufgabe übernommen, über die Noten zu sprechen, die Beethoven auf den fünfzehn Seiten in ungestümer Schrift zu Papier gebracht hat, das er beim Radieren mit dem Rasiermesser an mehreren Stellen durchlöcherte. Es war eine Erleichterung, dass Widmann einen ganz anderen Beethoven vorstellte, der sich aller humanistischen Dimensionierung verweigert.

Man muss ihn eigentlich sogar einen Unmenschen nennen, angesichts dessen, was er laut Widmanns Bericht den Musikern zumutet, die den „Alla danza tedesca“ überschriebenen Satz vom Blatt zu spielen versuchen, wobei es dafür auf den Unterschied zwischen dem handschriftlichen Urtext und handelsüblichen Notendrucken nicht ankommt. Er macht es den vier Instrumentalisten so schwer, als hätte er alle kollegiale Solidarität und sogar die gemeinsame Zugehörigkeit zur Menschengattung vergessen.

As if to reinforce the aura of the musical notation in the display case, with the exception of Hope, whose native language is not German, all of the afternoon’s speakers refrained from reading their prepared remarks. Ina Brandes, Minister for Culture and Science of North Rhine-Westphalia, took the microphone out of its holder for her greeting and took a demonstrative step on the small stage next to the music stand intended as a lectern. Widmann also had no manuscript. It would be impossible to print his celebratory lecture here in the newspaper because far more would be lost than the many musical examples that Widmann, who is usually heard playing the clarinet in the concert hall, offered on the grand piano.

A second, commented performance

The lecture was essentially a second, commented performance of the movement initially played by the young Avada String Quartet, which Beethoven said was made in the style of a German dance, a kind of critical live edition. Alternative versions improvised by Widmann included: Using several examples, he demonstrated how Beethoven could have made things minimally and thus significantly easier for the musicians by changing the musical text. There is a place where Beethoven puts a sixteenth note where you would expect an eighth note. And this unexpectedly halved note then gets an accent, so that Beethoven “emphasizes in a place where no human being would emphasize.”

Replacing eighth notes with sixteenth notes creates a sixteenth notice break, and based on Widmann, when studying these notes, the musicians already see and know what to anticipate throughout the efficiency: their extreme calls for are intentional and are then in all probability even what is meant to be offered . “For us musicians, when we read it, it gets in the way: I can’t continue playing on time.” Widmann performs it, and now the expression takes on one thing human, albeit all too human: Yes, the damaged outlier sounds “almost like a Hiccup.”

In the type of a German dance, that’s to say easy on the skin: in three-eighth time. According to Widmann, this measurement is barely right for the 2 violins; What Beethoven wrote for viola and cello sounds as if it have been in three-four time. Widmann imagines how the sentence might need been obtained by the primary quartet that bought their fingers on the manuscript: “We got a piece in three-four time from this Beethoven, but it’s in three-eighth time, how do we play it?” Widmann stays The reply will not be responsible: “Neither nor.” Because within the battle between the 2 three-bars, the second bar time is emphasised.

Beethoven nearly destroys the musical materials

Widmann defined instructively firstly that this system already seems in earlier actions of op. 130. “What is important,” the music pupil learns and, based on Widmann, the composition pupil should not neglect, “is the difficult beats.” Beethoven “totally undermines” this normal; He treats the musical materials “in an almost destructive way” by emphasizing it opposite to the meter whereas sustaining the meter system. In Widmann’s studying, the writing preserves the damaging intention. If Beethoven had written it otherwise, it could be “ten times easier to play; “The one doesn’t even appear anymore.”

Widmann calls the start of the 4th motion “what he throws between our legs as musicians”. The listener was in a position to join the interpretation of the act of violence with what they knew from college classes or live performance packages. Why isn’t “German dance” written above the sentence? In the primary bars “usually something is introduced and then it is varied, but that is already so much variation”. For the viewers’s amusement, Widmann additionally performs the German dance, which may have been the premise for the tearing variations, adopted by a transposition right into a Viennese waltz. While the musicians are pushed to the boundaries of their talents, the composer reveals that he has mastered all of the steps and jumps – proper and left, open and closed, by no means fairly as desired.

Widmann allowed himself to be carried away into an anthropological hypothesis by his abbreviated presentation of the work, which included vocal interludes, however the inscrutableness remained tempered by comedy: “What does Beethoven want to say about the German: that it can only end in stumbling? What is the character of the one dancing there?”

There was a contact of the Vienna Congress over the reception since you noticed so many faces from the nice outdated days of the Bonn Republic: Monika Wulf-Mathies, Peer Steinbrück, Norbert Röttgen, and likewise Steinbrück’s State Secretary Werner Gatzer. According to stories, the deal, which was carried out with out the involvement of the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, is the most costly acquisition the Beethoven House has ever made.

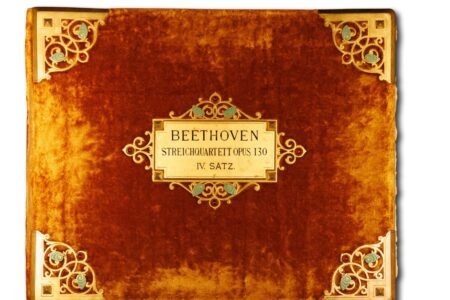

The piece comes from the gathering of the Viennese lawyer Heinrich Steger (1854 to 1929), chairman of the Society of Music Friends. He had ten Beethoven autographs sure in velvet and provided the gathering on the market to the Beethoven House, which solely bought 4 items. The initially spurned items have been acquired one after the opposite – the final being “Alla danza tedesca”. This piece was taken by the Germans from the Petschek household of Jewish collectors in Aussig after 1938 and remained in Brno in 1945. The Czech state returned the autograph to the Petschek household in 2022, which has now given it to Bonn.

From June onwards, the manuscript and its historical past would be the topic of an exhibition within the Beethoven House. The administration ought to contemplate offering Jörg Widmann’s lecture not less than as an audio monitor – an AI may even perhaps create an avatar of Beethoven’s congenial colleague.

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/buehne-und-konzert/bonner-beethoven-haus-kauft-quartett-autograph-op-130-110218911.html